Speaking at Reed College in 1965, a Portland Nazi floated the idea of building a barbed-wire topped wall along the entire Mexican border. The audience erupted in dismissive laughter. Not so funny now.

Sometimes history does more than just rhyme

“We’ve got to build a white citadel. We’ve got to build a wall. We’re gonna start where the Rio Grande goes into the Gulf of Mexico and it’s going to extend to Baja California. It’s going to be approximately 100 feet high and 50 feet thick. And it’s going to be topped with barbed wire and it’s going to have booby traps, it’s going to have about three miles of plowed earth & barbed wire on either side. It’s going to be mined. As a matter of fact it’s going to be so dense that if my plan or my projected concept is realized people will not be able to enter the United States of America, they will not even be able to crawl across the plowed area without losing between two and three feet." —Edmund Crump, leader of the Portland-based National Party of America. Statement made at a 16 February 1965 speech delivered at Reed College, a recording of which is housed at the Reed College Library Special Collections.

“Privately, the president had often talked about fortifying a border wall with a water-filled trench, stocked with snakes or alligators, prompting aides to seek a cost estimate. He wanted the wall electrified, with spikes on top that could pierce human flesh. After publicly suggesting that soldiers shoot migrants if they threw rocks, the president backed off when his staff told him that was illegal. But later in a meeting, aides recalled, he suggested that they shoot migrants in the legs to slow them down. That’s not allowed either, they told him.” —New York Times report on President Donald Trump’s ideas for militarizing the border, 1 October 2019.

You can probably imagine how my jaw dropped when, sitting in the Reed College Special Collections reading room listening to a recording of a 1965 speech delivered by one of Walter Huss’s proteges, I heard that arrestingly familiar “build a wall” proposal pour through the headphones. The speaker was Edmund Crump, the 20 year old head of a short-lived organization called the National Party. I recently gave a talk about that group, and what follows is a very abbreviated summary of who they were and an assessment of how we should (and should not) think about this moment of uncanny familiarity from 1965.

The tl;dr takeaway is that Donald Trump absolutely did not get the idea for his border wall from a Portland fascist ca. 1965, but the white nationalist wall rhetoric deployed by both Donald Trump (b. 1946) and Edmund Crump (b. 1945) emerged out of and contributed to a distinctively American fascist tradition that threads like a rhizomatic structure through the last 100 years of US political history. We ignore that history at our peril, because we’re still living inside of it, whether we are cognizant of and informed about it or not.

Between 1964 and 1966, about twenty brown-shirted and jackbooted fascists who called themselves “The National Party of America” staged dozens of direct actions in Portland. They picketed Jewish stores, the offices of the city’s two “Jewish-controlled” newspapers, and a host of civic events brandishing signs that said “Another Jew Deal” or “Death to Traitors—Join the N.P.A.” or “Communism is Judaism.” When George Wallace came to Portland in January of 1964, the newly formed National Party showed up to picket in support of Wallace along with a handful of other white supremacists. They spat racist epithets at the 150 or so civil rights activists who had shown up to protest against the arch segregationist Alabama governor. One of the adults who joined the teenaged National Party founders on that pro-George Wallace picket line was one of their mentors, a 45 year old anti-Communist minister named Walter Huss who would become the chair of the OR GOP fourteen years later in 1978.

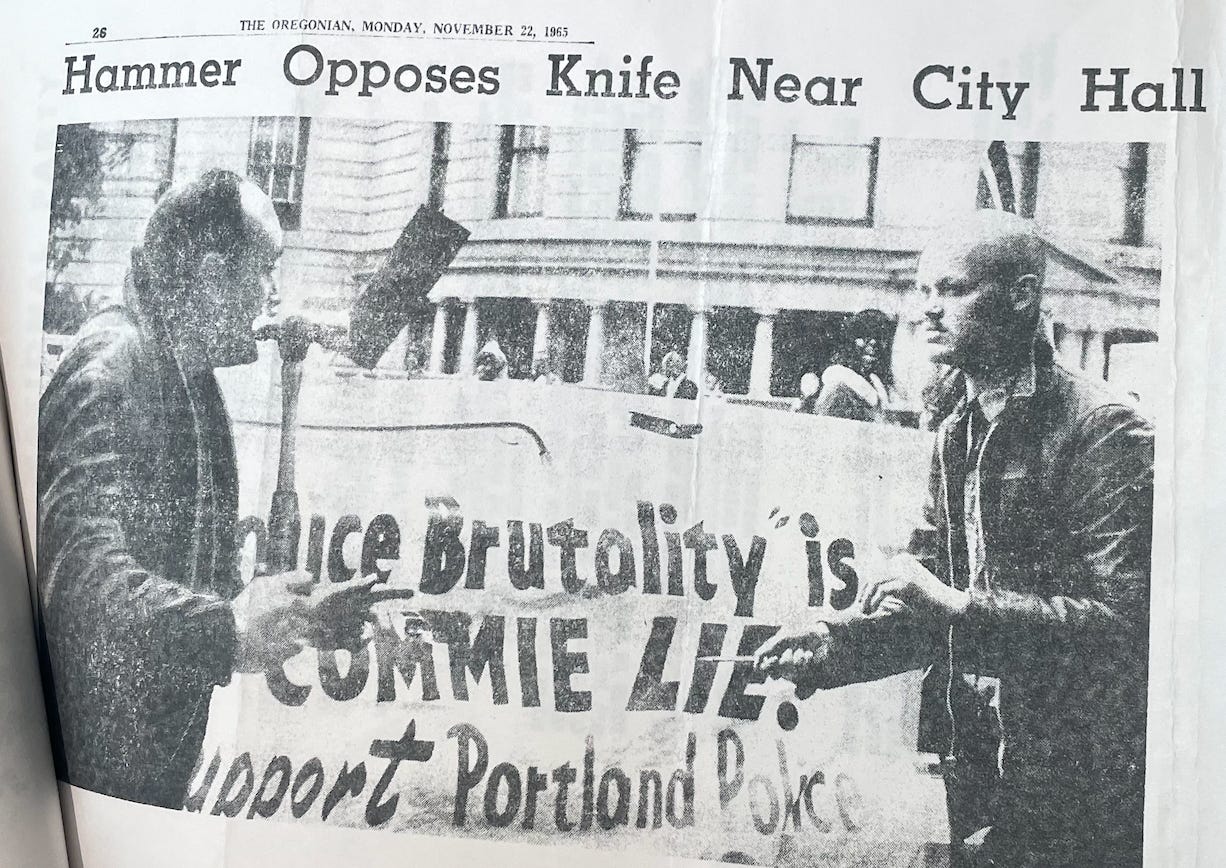

In November of 1965, when a group of about 50 Black activists marched a few miles from the Albina neighborhood to city hall to protest racist police violence, the National Party drove menacingly beside them the entire way in their Confederate Flag festooned pickup truck. When a homeless man smashed the window of the pickup, a National Party leader grabbed a knife from the glove compartment and was swiftly arrested by the police.

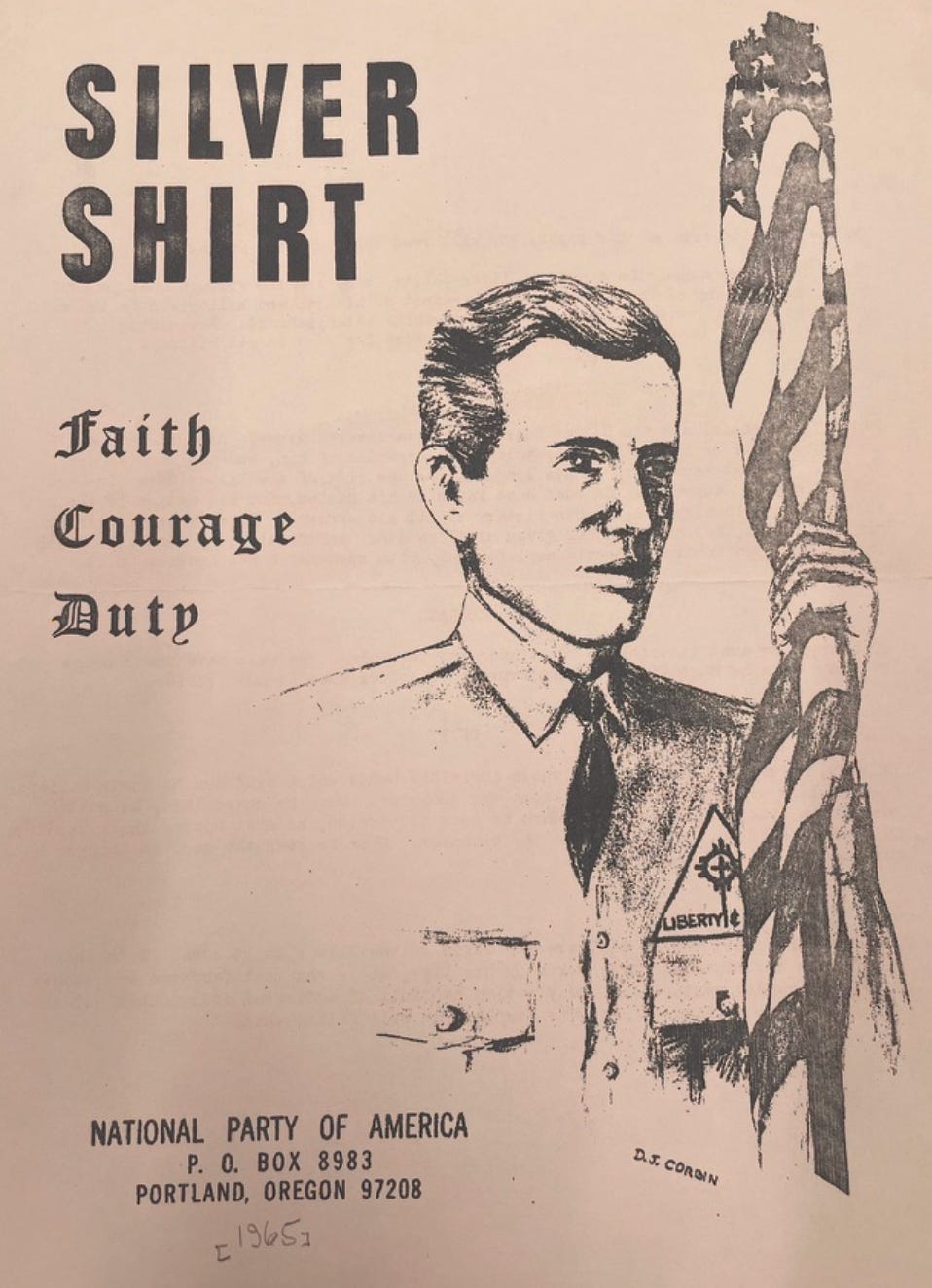

The two young leaders of the National Party, Roger Gerber and Edmund Crump, cut their teeth as political activists in 1961 when, as high school students and longtime neighbors on the 8300 block of SE Bush St., they started attending “conservative, anti-communist” meetings at Walter Huss’s SE Portland Freedom Center. In the early 1960s they also became acquainted with two of Huss’s fascist associates—Dale Benjamin (a KKK preacher in the 1920s, Gerald LK Smith acolyte in the 40s, and National States Rights Party leader in the 1960s), and Sylvester Ehr (a Silver Shirt and America Firster from the 1930s and future leader of the Posse Comitatus movement in the 1970s). It was through these intergenerational ties that the fascist practices and ideas that had flourished in 1930s Portland reproduced themselves on the city’s streets in the 1960s.

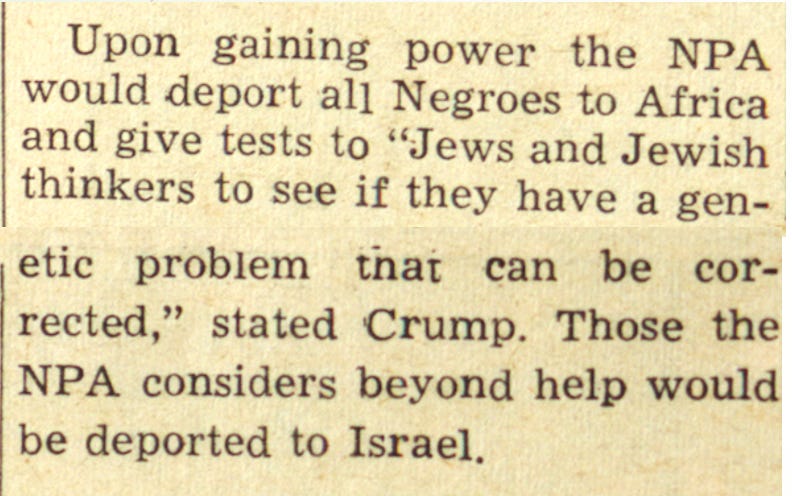

After Goldwater’s loss in 1964, Crump and Gerber’s National Party adopted an even more confrontational and unapologetically white nationalist and antisemitic style of “conservative” political activism. They donned colored uniform shirts and jackboots, and modeled themselves after the fascist Silver Shirts of the 1930s whose leader, William Dudley Pelley, referred to himself as the “American Hitler.” The central premise of the 1930s Silver Shirt movement was that Communism was a Jewish conspiracy. If one believed that to be true, then it followed that eliminating the Communist threat meant eliminating Jews. On this point, the National Party of the 1960s agreed entirely, though they recognized that they didn’t have the political clout yet to carry out this project of reclaiming America from the Jewish/Communist menace in the same genocidal way Hitler had attempted to do in Germany. The National Party, for the time being, was content to deport all Black Americans to Africa and deport only “genetically irredeemable” Jews to Israel.

On February 9, 1965, the National Party staged its most confrontational action to date when they goose stepped down the aisle of a PTA meeting at a SW Portland high school where Assistant Attorney General J. Belton Hamilton (one of Oregon’s few Black public officials at the time) was giving a talk entitled “Resistance to Integration—Why?” The young uniform-shirted fascists hissed racist and antisemitic slurs at the speakers on the dais while a greek chorus of about a dozen older white women sitting near them joined in.

The Oregonian, 21 February 1965

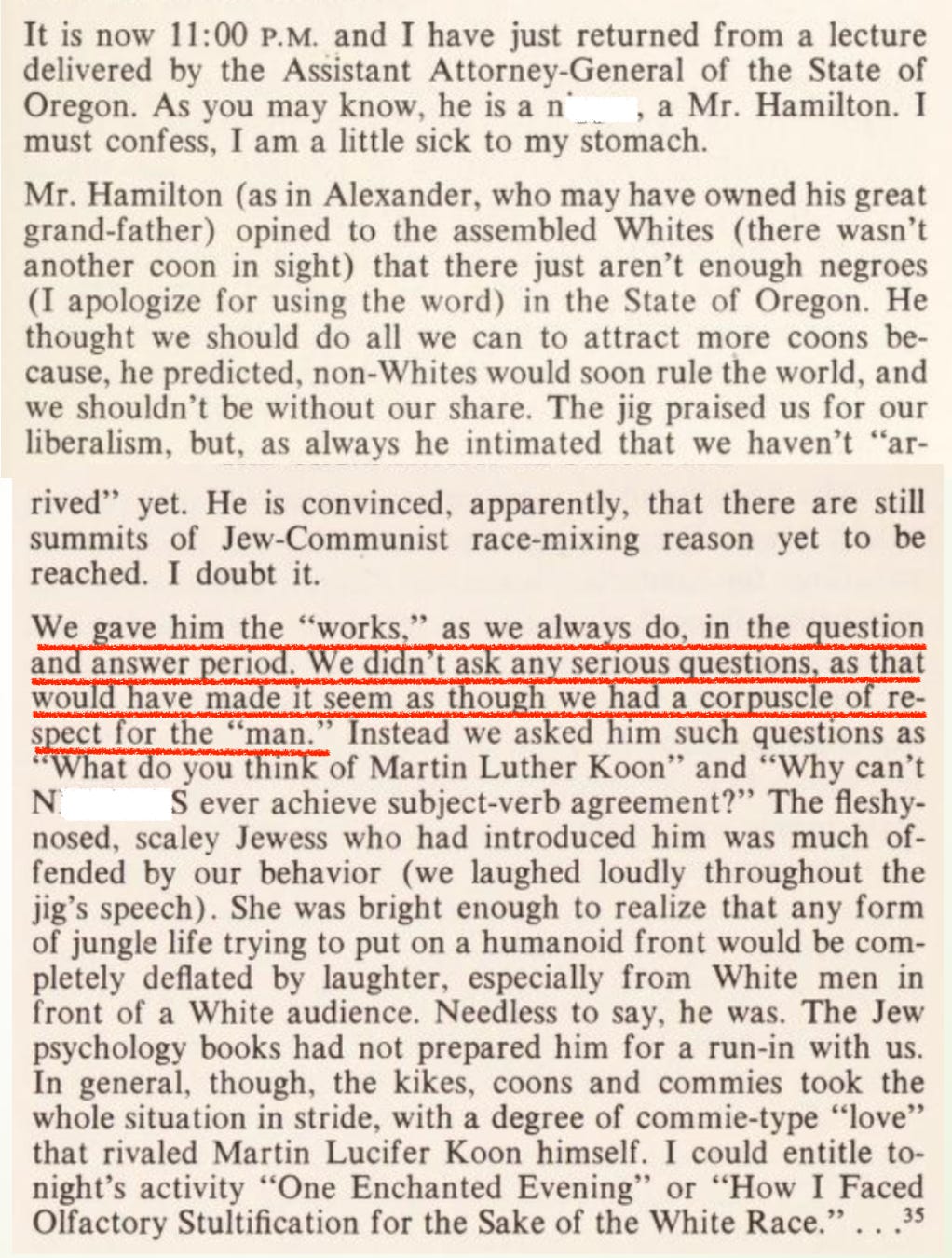

Below is how National Party leader Edmund Crump depicted that meeting in a message he sent out to his mailing list of supporters. As you can see, unlike his much more politically savvy (but equally racist and antisemitic) mentor Walter Huss, Crump made no effort to mask or sugarcoat his racism and antisemitism. In fact, he positively luxuriated in it.

As the underlined section shows, the National Party’s politics was about genocidal dehumanization, not democratic engagement. In an era when the Civil Rights Movement sought to win the hearts and minds of all Americans so as to redeem the promissory note of equal citizenship and multi-racial democracy, the National Party insisted that the only historical legacy any contemporary American need honor was the legacy of white Christian supremacy. Anything else was Communism, and was probably the brainchild of some Jew like Karl Marx (who was not Jewish). This is what I mean when I refer to the National Party as a fascist organization, regardless of whether they themselves would have owned that terminology.

In the interest of not allowing Crump’s racist bile to be the last word on J. Belton Hamilton, I’ll quickly note that Hamilton was a child of Mississippi sharecroppers who was awarded a Purple Heart for fighting Nazis in WWII. He then earned a BA from Stanford and a JD from Lewis and Clark before marrying Midori Minamoto Hamilton, whose family had been interned in Idaho during WWII. So when confronted with the adolescent bluster of these preening Portland Nazis who pestered him in February 1965, I imagine Assistant Attorney General J. Belton Hamilton was well prepared for that moment. Unfortunately, I’ve yet to find any record of Hamilton’s response to his fascist hecklers.

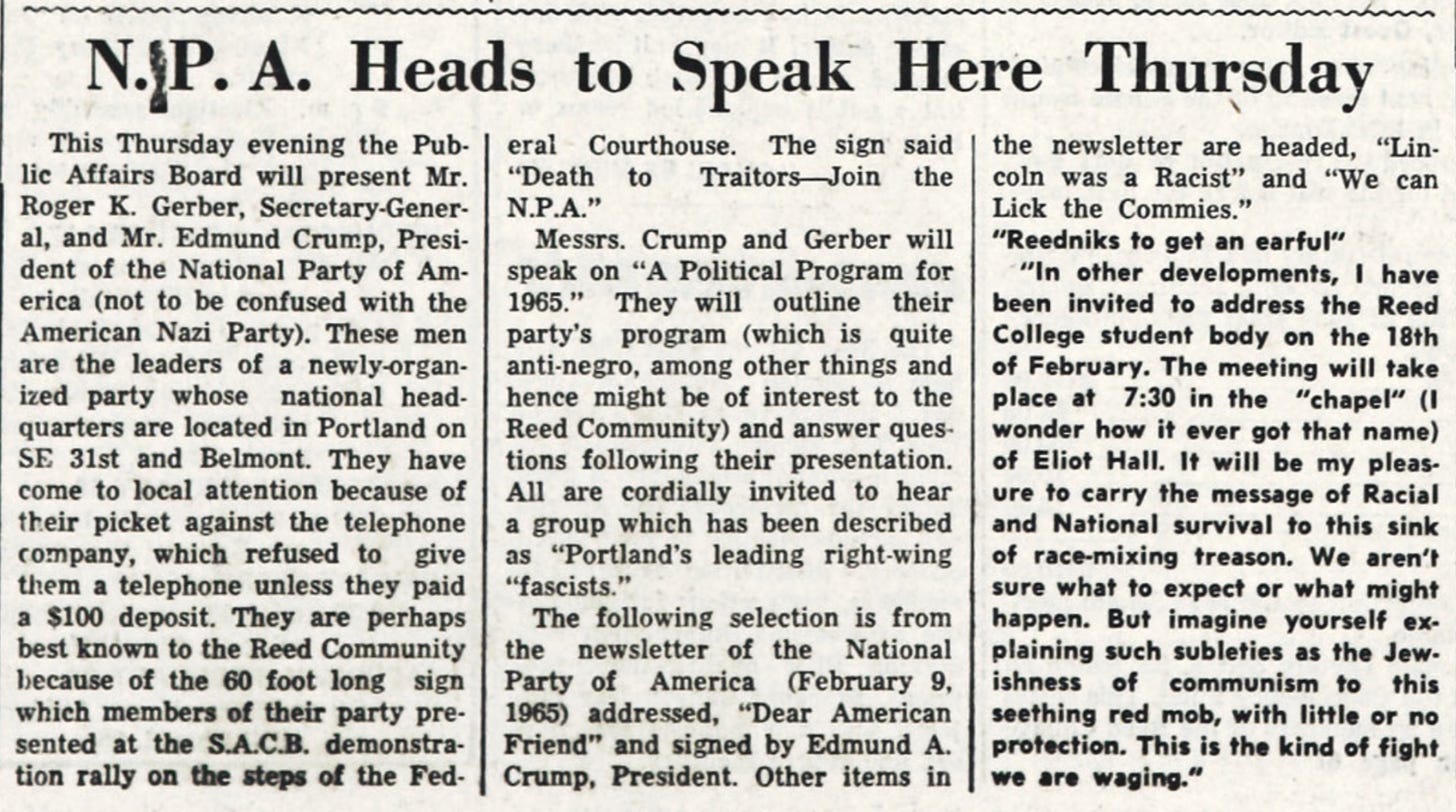

Exactly one week after disrupting J. Belton Hamilton’s speech at that PTA meeting, National Party leaders Crump and Gerber gave an invited talk at Portland’s Reed College, “that sink of race-mixing treason.”

The Quest, 15 February 1965. Reed College Library, Special Collections.

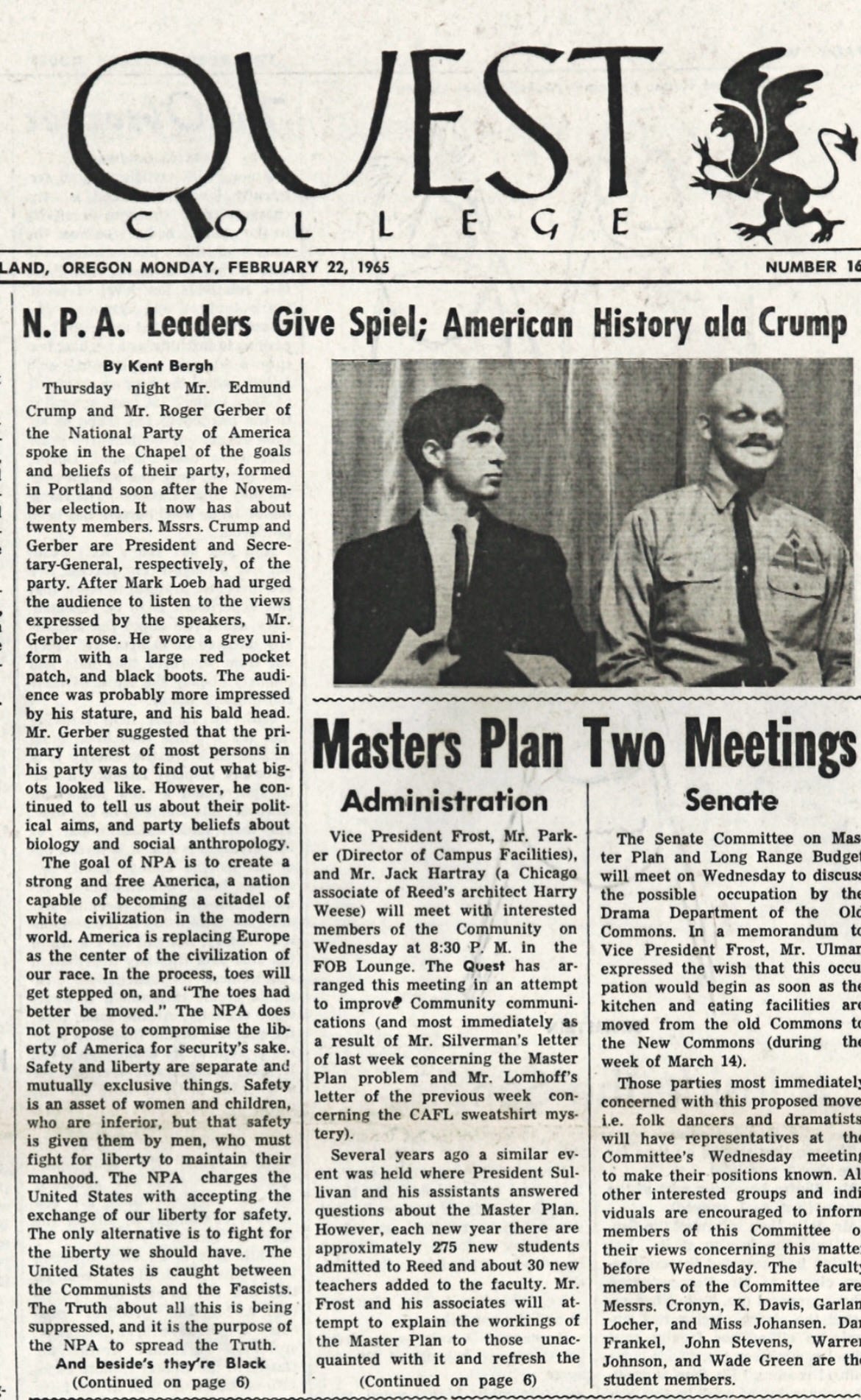

A recording of the event is housed in the Special Collections at Reed Library and I got a chance to listen to most of it yesterday (I’ll be returning soon to listen to the rest of it). The quote about the border wall with which this post began is a transcription of part of their speech. Despite Crump’s prediction that he and Gerber would be besieged by a “seething red mob, with little or no protection,” the recording of the event reveals that the reception they received was quite civil, if often sprinkled with waves of mocking laughter. After Gerber and Crump spoke, Reed students peppered them with questions that deftly pointed out the contradictions, absurdities, and genocidal logic of their political project. The event had the feel of a field trip to the zoo, with Reed students getting a chance to gawk at, up close and personal, two actual fascists in the flesh. Such events were common in the mid-1960s with America’s most famous Nazi, George Lincoln Rockwell, constantly traveling the college speaker circuit creating similar spectacles at scores of universities across the nation.

The impression I got from the recording of this Reed event is that Crump and Gerber did not change a single mind in the audience, and that the audience considered them to be relatively harmless, poorly educated bigots and kooks. (When Crump mispronounced Nietzsche’s name, for example, a ripple of condescending laughter coursed through the audience.) For their part, Crump and Gerber gave as good as they got. They seemed to enjoy sparring with the Reedies who they considered to be stuck up pinko fools, using the event as an opportunity to sharpen their rhetoric by engaging with critics.

Reed College, Special Collections.

A few minutes after Crump proposed building a wall along the border with Mexico, he stated that once America had become “a white citadel” it would be important to “strengthen our immigration laws.” He said that no more than 5000 immigrants should be allowed in per year. He complained that “right now there are 3 million people in the United States illegally,” and that was why he thought it was so important to immediately begin building “the wall.”

According to Crump, the National Party’s central focus was to “protect the white race and white civilization by law. Let’s establish laws that will ensure and guarantee the existence of the white race into the future and the civilization which is the fruit of the white race.” Note how similar this 1965 statement is to the notorious “14 words” coined by David Lane in the late 1980s and which subsequently became a central mantra in American neo-Nazi/fascist political culture. Unfortunately, this talk of a great white civilization supposedly being systematically undermined by alien outsiders has now spilled far beyond the once fairly narrow bounds of the American neo-Nazi movement.

What to make of these echoes, this historical rhyming?

I’m not an expert on the history of the US Mexico border, but from what I’ve been able to gather in the research I’ve done so far, it appears that Crump’s talk of building a wall was quite unusual in 1965. The first time anything resembling a wall was built on the southern US border was in the late 1970s, and then the next major wave of wall building occurred during the Clinton administration in the mid-1990s. When fascists David Duke and Tom Metzger demagogued about the border in the 1980s and 1990s (eventually joined by their more mainstream anti-immigrant comrade Pat Buchanan), I’m sure they had no idea they were echoing points made by their 1960s fascist predecessors from Portland. Regardless, their white nationalism emerged out of the same soil as Edmund Crump’s. Metzger and Duke were both roughly Crump’s age, and both had been socialized into the same variety of “anti-communist,” John Birch-adjacent conservatism in the 1960s. Looking forward to today, it is precisely that Pat Buchanan variety of Christian Nationalist, “America First” Republicanism that Donald Trump tapped into during his 2016 run for the GOP nomination. Sadistic talk of border walls may have been the preserve of only a few scattered fascists in the 1960s and then a small subset of Republicans and “conservatives” in the 1980s and 90s…but such talk has now become entirely normalized in today’s fully Trumpified GOP.

So the point here is not that Edmund Crump is somehow the father of contemporary right wing border demagoguery. There is zero chance Donald Trump got the idea to build a sadistic, killing wall on the border with Mexico from an obscure 1965 talk by Portland fascist Edmund Crump.

The line from Crump to Trump passes not directly, but in subterranean fashion through the razor-edged right wing nationalism they shared, especially its laments about whiteness besieged and its hopeful vision of a restored era of white American greatness untroubled by racialized others and their “globalist puppet masters” who threaten to “poison our blood.” This thread of white nationalism courses through the post WWII era like a rhizome, rooted in centuries of white supremacy and only partially kept submerged beneath the surface of American political discourse by the tenuous, Cold War era “consensus” that the US was an as-yet imperfectly realized multi-racial and religiously pluralistic democracy. The unapologetic white nationalism and antisemitism expressed by Crump and Gerber at that 1965 Reed event was simultaneously heretical (hence the students’ prurient curiosity in coming to witness it), but also not nearly as vestigial as the confidently derisive laughter of that Reed audience seemed to imply.

In 1991, Roger Griffin, a leading scholar of fascism, boiled the essence of that phenomenon down to “palingenetic ultranationalist populism.” “Palingenetic” is a reference not to Sarah Palin (though that would actually work fairly well), but rather to the idea of rebirth. In the past the nation was great, the story goes, but now it is besieged by parasitic enemies above you (Jews/Soros, globalists, government bureaucrats, scientific experts, medical professionals, college professors, the deep state, elites of all sorts) and parasitic enemies below you (immigrants, welfare cheats, homeless people, LGBTQ folks who will cancel you if you don’t use the correct pronouns, coddled criminals, etc.). Both sets of parasites are secretly conspiring together to destroy you, the hard-working, salt-of-the-earth Americans to whom the country used to belong. The nation needs a strong leader to vanquish these enemies, or at least put them in their place. Then, and only then, can we return to our natural state of national greatness. But the enemies of the people are tremendously powerful. Are you ready to do what it takes?

Nationalism does not necessarily lead to fascistic forms of politics like that. There are more and less fascistic ways in which citizens have expressed and enacted their nationalistic impulses over the centuries. The danger heightens when the dehumanizing and conspiratorial talk of others as immensely powerful “enemies” intensifies. This is how Primo Levi put it in his 1947 memoir of his time at Auschwitz:

“Many people - many nations - can find themselves holding, more or less wittingly, that 'every stranger is an enemy'. For the most part this conviction lies deep down like some latent infection; it betrays itself only in random, disconnected acts, and does not lie at the base of a system of reason. But when this does come about, when the unspoken dogma becomes the major premise in a syllogism, then, at the end of the chain, there is the [gulag]. Here is the product of a conception of the world carried rigorously to its logical conclusion; so long as the conception subsists, the conclusion remains to threaten us. The story of the death camps should be understood by everyone as a sinister alarm-signal.”

Crump’s 1965 speech where he floated the then-kooky idea of building a murderous border wall provided a fairly clear-eyed road map for how he imagined his vision of a white Christian America might come into existence.

“In Oregon if you poll 10% of the voters you are considered a major party. We are localizing our efforts. We’re not making any great attempt to go all over the country and have five people in every leading city in the country. We’re trying to build a solid base of support here which we believe is in keeping with the way other organizations of our type have built mass movements like for instance Martin Luther, Gutenberg, or the Russian Revolution. They start in one place and spread out…I believe that by 1966 or 1968 we can poll ten to fifteen percent of the vote in Multnomah county….By 1968 we can have a nationalist administration set up in Oregon. At that point we can establish ourselves not as neo-Nazis or hate men or something that’s under the rug or something that doesn’t believe in American principles…see, this would all be washed aside, and then from the state of Oregon we would have ambitions in probably California next depending on the minority situation there, and various other parts of the country. I don’t know whether the east coast would be the last to go, I think New York City probably would be the…[laughter]…”

That laughter, and the way Crump kind of trailed off once he started imagining how to get NYC on board with the sort of White Christian Nationalism that was a minority persuasion in even very White Christian Oregon, tells us something important. Crump recognized that there was a constituency out there for his message, if only he could get Americans to stop thinking of him as a Nazi or a hater, but rather just as a lover of America and his fellow white people! Indeed, Crump’s mentor Walter Huss succeeded in riding a slightly more watered-down version of that message into the chairmanship of the Oregon Republican Party after diligently organizing precinct captains in every county in the state for over a decade. It could be done, but the tough part was implementing this fascistic vision of a White Christian America in a nation where both parties, the mainstream media, and the courts were at least nominally committed to the idea that the US was a multi-racial and religiously pluralistic democracy. But what if a political party could come into power that rejected those two premises? And what if you could build an alternative mediascape that treated multi-racial democracy and religious pluralism as un-American, rather than the epitome of American-ness?

Crump and Gerber left the world of political struggle in 1966. Their National Party fell into the dustbin of history. The only extant copies of their materials laid undisturbed in a folder at the Oregon Historical Society until I looked at them a few months ago.

But Walter Huss, the mentor to these National Party fascists, stayed in the fight his entire life, setting as his goal the capture of the Republican Party for his White Christian supremacist vision of the American future. While Huss died in 2006 in the midst of what he considered to be a profoundly disappointing GWBush administration, I’ve been able to track down several of his close political associates who are still alive. You’ll never guess what politician every single one of them avidly supports—that’s right, the “build the wall” guy.

This country is so messed up.