I’ve acquired many new subscribers over the past week (thanks, I think, to a recommendation from Kevin Kruse who recently joined Substack), so for those newcomers, here’s a quick description of what this newsletter is about. I’ve spent the past two years researching the career of Walter Huss, a far right grassroots activist in Oregon with ties to neo-Nazis and right wing domestic terrorists who shocked the world when he won the election for chair of the Oregon Republican Party in 1978. He was politically active from the late 1950s into the early 2000s, and though he never scored any political victories (aside from becoming OR GOP chair for a year before being ousted), he played a significant role in pushing the OR GOP away from the moderates and liberals like Mark Hatfield and Tom McCall who’d dominated it in the 1960s and 70s, and toward the far right fringes where that state party has resided for at least the past three decades. Huss’s story (as I’ve uncovered it in the 57 boxes of archival material he left behind) has much to tell us about 1) the deep roots of Trumpism and 2) the important role that local far right activists played in building a conservative movement with a political culture that had, by 2016, been ripened up for a fairly easy takeover by an illiberal populist authoritarian like Trump.

In this installment of Rightlandia I’ll tell the story of Dale Benjamin, one of the innumerable grassroots far right activists whose lives intersected with Huss’s. To my knowledge, I am the only person alive who knows anything about Dale Benjamin, but soon you too dear reader can join me in those illustrious ranks. To paraphrase comedian Neil Innes, I’ve suffered for my research into the American far right, and now it’s your turn.

[Warning: this newsletter contains a discussion of sexual violence against children.]

Dale Benjamin was a type of political actor we’ve unfortunately become quite familiar with in our social media age. He was an angry racist troll who identified a fragile democratic consensus around the value of religious pluralism and multi-racial democracy, and said “fuck that, I’m going to build a career out of opposing that tenuous consensus and then claim noble Christian victimhood when people in positions of influence or authority criticize me for being a racist troll.” From his time in the KKK in the 1920s to his leadership of the Oregon chapter of the National States Rights Party in the 1960s, only a handful of his fellow Americans ever regarded him as an admirable leader or joined the organizations he led. Like Walter Huss, he never won an election or influenced the passage of any legislation. Nevertheless, his actions and the coverage those actions got in the press breathed life into what many Americans wrongly thought was the gradually dissipating force of white Christian supremacy in modern America. If Dale Benjamin had just been a “lone wolf” actor writing racist screeds in his basement, then there’d be no reason to tell his story. But Benjamin’s career as an outspoken racist evangelist reveals the tip of a resilient far right cultural iceberg that many of his liberal and moderate white contemporaries failed (or refused) to perceive.

Benjamin first came on my radar screen when I read this article about Walter Huss in the [Salem] Capital Journal of November 21, 1963.

The backstory here is that Walter Huss had applied to this same committee for a fundraising permit in 1961 and had been turned down. The city denied his application to raise funds to refurbish his newly-founded, anti-Communist "Freedom Center” because that "center" happened to be located in his home and, well, it looked a lot like Huss was raising “charity” money to do repairs on his house. In the public hearing over this denial in 1961, which was broadcast live on local TV because Huss had made such a stink about it, it emerged that even though Huss called himself a professional educator about the evils of Communism, he could not accurately answer even the most basic factual questions about the topic. Huss dealt with this humiliation in the way he would deal with every subsequent humiliation over the next 40 years—he lashed out at the “establishment politicians” who had “unfairly” victimized him. He also lashed out at the marginalized groups (like the NAACP) who he claimed were the puppet masters pulling the strings of that establishment and encouraging them to oppress and silence upstanding “real American” Christian Patriots like him.

This is why Huss showed up at that boring bureaucratic meeting in 1963 along with his associate Dale Benjamin. It was a public meeting so they had a right to be there, but everyone knew they came solely to troll the committee charged with approving the NAACP’s routine fundraising application. Even though Huss’s effort to throw a wrench in the normal workings of the city’s bureaucratic process failed—the NAACP was granted their permit as usual—he still made life just a little more difficult for this civil rights organization in lily-white Oregon. It’s worth noting that this was two months after four Black girls had been murdered by a white supremacist bombing at a Birmingham church, three months after MLK’s “I have a dream” speech at the March on Washington, and the night before JFK’s assassination (more on that later).

When I noticed that Dale Benjamin had joined Huss’s protest against the NAACP it made me wonder who that Benjamin guy was…and well…that took me all sorts of unexpected places. First it took me to Scio, NY, a town of about 1000 people 80 miles SW of Buffalo. In October 1924 a Spokane, WA based preacher named Dale Benjamin, a WWI vet and former football star from the University of Oregon, drove into Scio in a car emblazoned with the words “Keep Kalvin Koolidge” on the side. Benjamin began preaching in the Klan-friendly Divinity Protestant church to much acclaim, but within a few weeks three girls in that church accused him of sexual improprieties.

Evening Leader and Corning [NY] Daily Democrat, November 25, 1924.

In a move that might sound familiar, Benjamin proclaimed his innocence and insisted that the charges against him were part of a politically motivated witch hunt by people prejudiced against upstanding, patriotic Christian Klan members like him. One amazing detail in this story is that when the people of Scio ran Benjamin out of town they tarred and feathered his KKK car.

Buffalo Enquirer, November 25, 1924.

Benjamin’s sexual assault case took many twists and turns (including another accuser coming forward with even more serious charges and Benjamin’s attorney’s getting into legal trouble for falsifying affidavits on his behalf), but the end result was that Benjamin skipped bail and headed off for greener pastures where he hoped his previous reputation (and the long arm of the law) wouldn’t follow him.

Buffalo News, June 30, 1925

Benjamin next turns up in the archive a few months later in the little town of Millville, Delaware just outside of Bethany Beach. Benjamin led a revival at the previously moribund Church of Christ there. His nightly preaching brought in unprecedentedly huge crowds, Bible School records were broken, and soon his nightly audiences grew too big to be accommodated in the church’s building. Benjamin clearly had something about him that resonated with the people of Millville, DE in 1926. I think it’s safe to assume, however, that the people in the pews did not know about Benjamin’s recent past.

Milford [DE] Chronicle, February 12, 1926

Benjamin left Delaware sometime in 1926 and began preaching in Avis and Farmington, PA—two small towns 100 miles south of Scio, NY where he’d recently fled justice. Soon after he arrived in central Pennsylvania he was charged with “serious offenses against young girls of his congregation.” After investigating the charges, a judge declared Benjamin “insane” and a “moral pervert” and sentenced him to be confined in a mental hospital so that he would be “removed from society for the rest of his natural life, unless he should recover his normal state.” Some of his former congregants came to court to protest on Benjamin’s behalf, but the judge held firm. He was “convinced that no minister of the gospel could have committed the crimes charged to Rev. Benjamin and be sane.”

Evening Leader and Corning [NY} Daily Democrat, July 5, 1927

Here the archival trail goes cold (at least at this stage in my research), but at some point over the next 10 years Benjamin returned to Spokane, WA a free man. In 1936 he unsuccessfully ran for congress and endorsed third party candidate William Lemke for President. Benjamin was also one of the first people to greet Christian Nationalist and rabid antisemite Gerald LK Smith when he came to speak in Spokane. The trajectory from the 1920s KKK to a 1930s Gerald LK Smith/William Lemke supporter was a common and logical one.

Spokane Chronicle, October 31, 1936

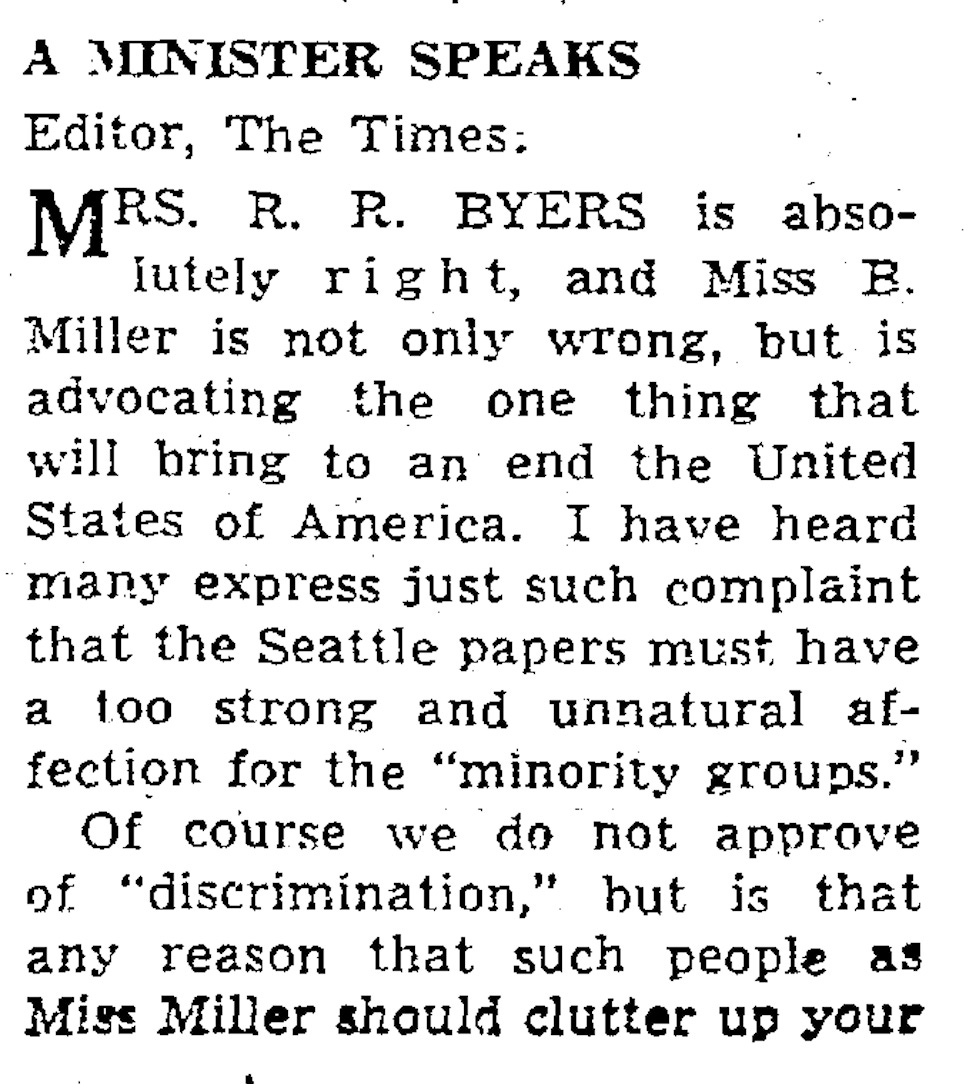

Sometime in the 1940s Benjamin moved to Seattle where he became an occasional contributor of racist letters to the editor like this one.

Seattle Times, September 30, 1945

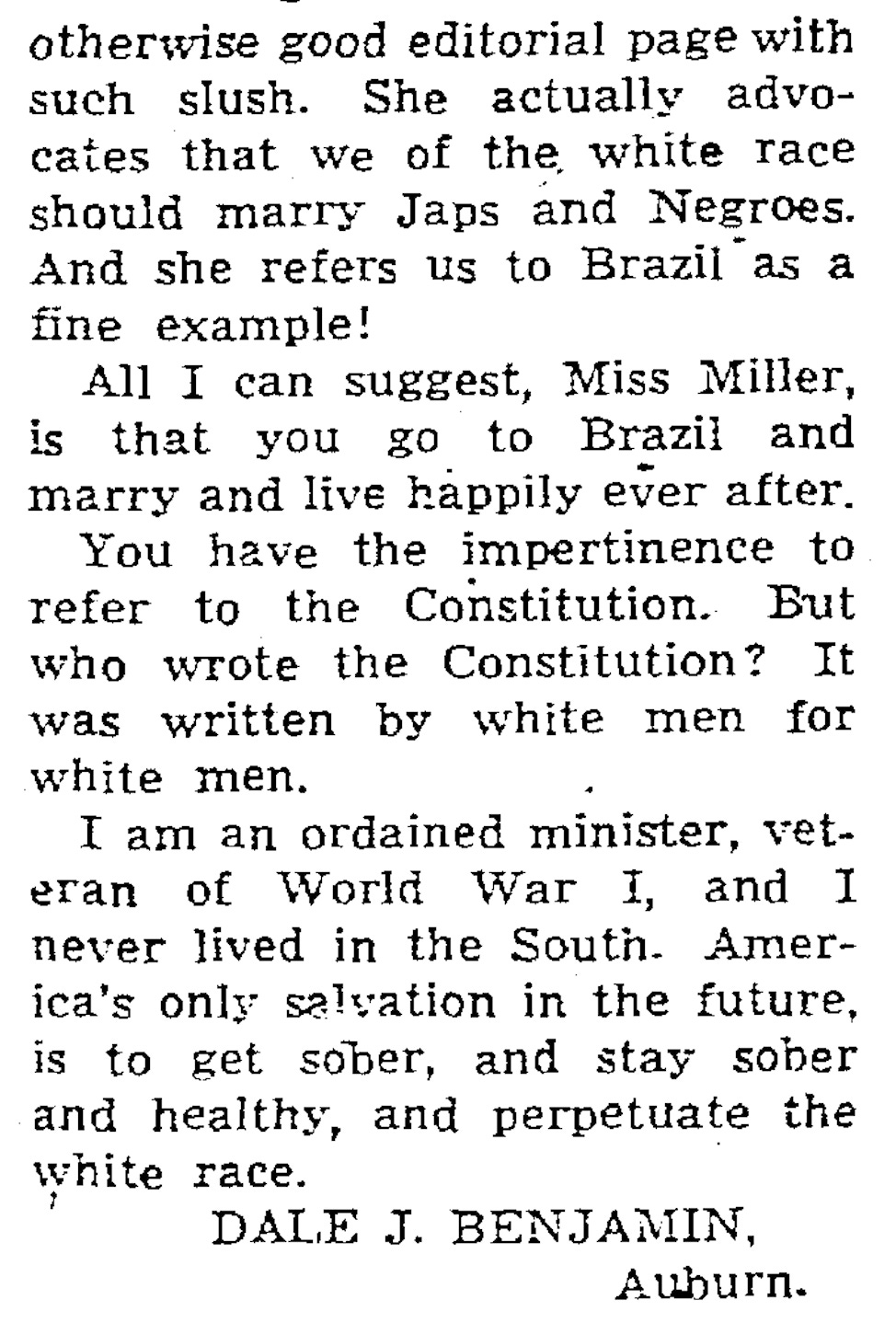

Despite the fact that Benjamin frequently got his racist letters printed in the newspaper, he was still convinced that the “Jewish-controlled” media refused to air “both sides” of the civil rights issue. Below we see Benjamin complaining in 1952 that Black people held a privileged position in Seattle while he, a white Protestant, was systemically stymied in his efforts to get his point of view aired.

Seattle Daily Times, September 6, 1952

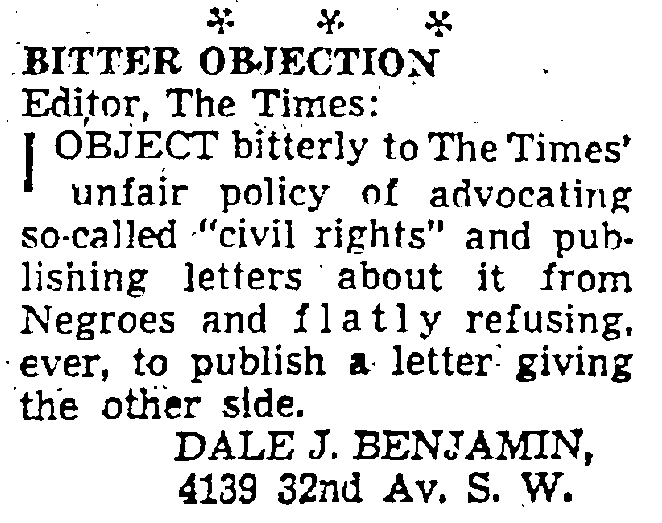

In 1954 Benjamin unsuccessfully ran for school board in Seattle, though he did get 4000 votes. His campaign focused on bringing the Bible and Christianity back into public school classrooms and returning to “old fashioned” methods of teaching “the basics.” Just like today, that “back to basics” language was code for “schools should stop teaching kids how to function effectively in a racially diverse and religiously pluralistic democracy because that might make them question the various bigotries their parents sought to instill in them.” The press coverage suggests that Benjamin did not foreground his longstanding ideas about white Christian supremacy, rather he merely presented himself as a Christian parent concerned about rising crime and immorality.

Seattle Daily Times, March 6, 1954

After losing the 1954 school board election, Benjamin got back into the itinerant minister business. He landed a position as a minister to a Church of Christ in Laurens, Iowa about 150 miles NW of Des Moines.. That didn’t last long, however, for less than a year after arriving in Iowa Benjamin wrote a screamingly racist letter to the editor of the Des Moines Tribune and then was dismissed by his congregation and publicly rebuked by them in that same newspaper.

Des Moines Tribune, May 6, 1955

Des Moines Tribune, May 18, 1955

After his brief and unsuccessful stint in Iowa, Benjamin returned to the Pacific Northwest. In October of 1955 he wrote a letter to the editor of The Oregonian weighing in on the acquittal of Emmet Till’s murderers. Berating a woman who’d expressed her sense of national shame about what happened to Till, Benjamin (who claims he does not condone murder) went on to argue that he understood why people would get mad at the behavior of a young person like Till and maybe people in the North should stop lecturing white Southerners about how they should run their communities because white Mississippians didn’t tell Oregonians how to behave.

The Oregonian, October 6, 1955

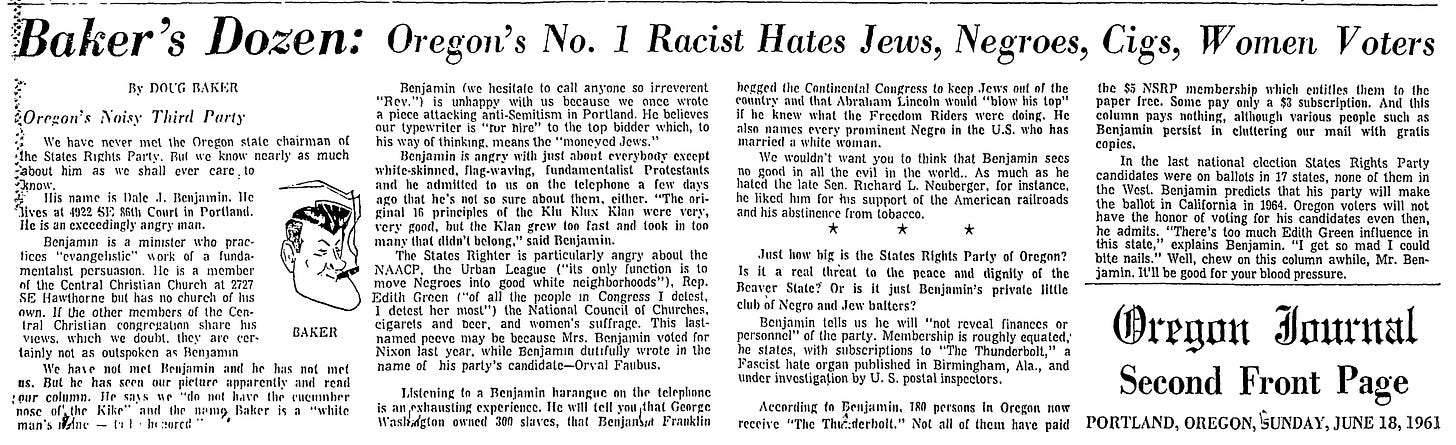

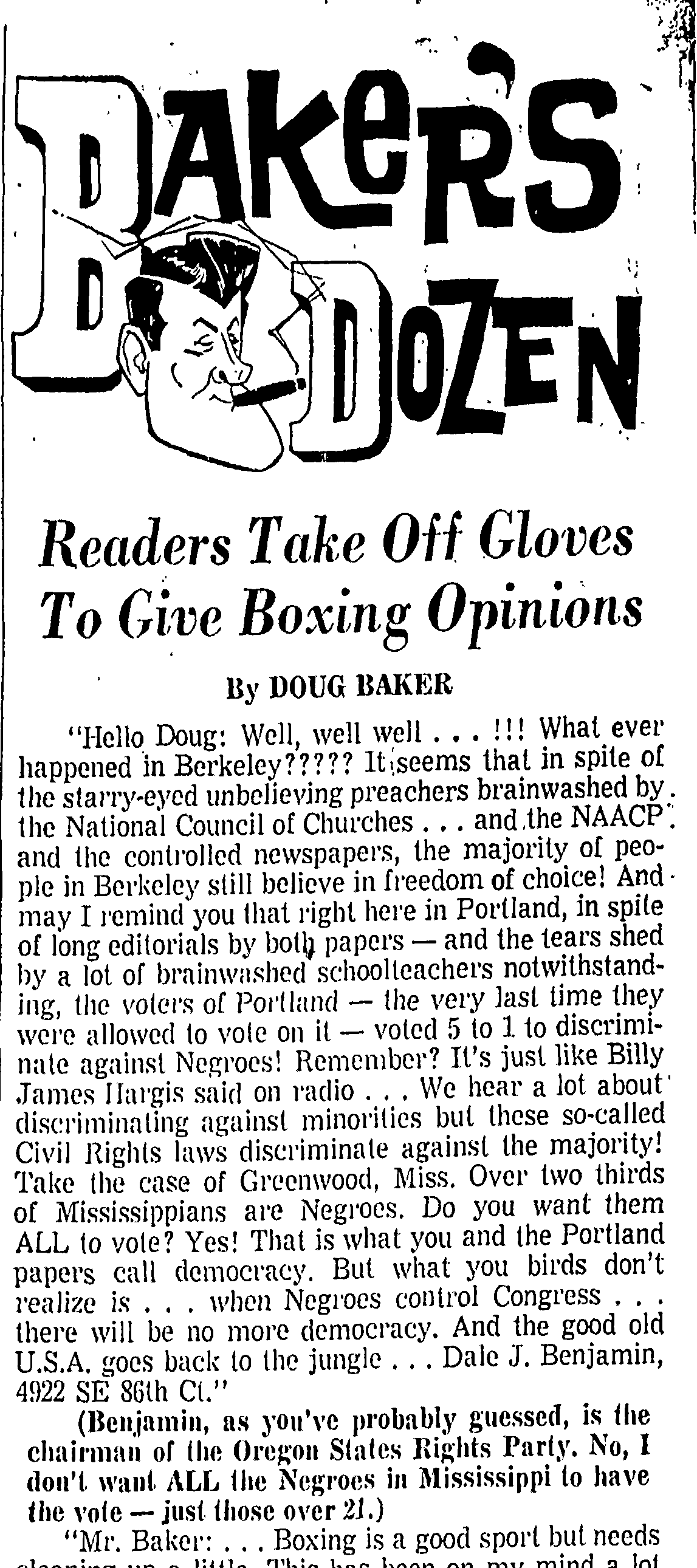

One of the stories that dominated the national press in the early 1960s was the resurgence of the far right in the form of the John Birch Society and other similarly anti-communist and anti-civil rights groups. Walter Huss drew some attention in the local press as Portland’s local iteration of this far right resurgence, but Dale Benjamin became the particular favorite of one of Portland’s local columnists, Doug Baker. While Baker intended to draw derisive attention to Benjamin’s racism, Benjamin seemed happy to get the publicity, eagerly sparring with Baker in the columns of the Oregon Journal and making his case that in modern day America it was “the majority” of white Christian Patriots like him who were being discriminated against by “the controlled media” and a radical left federal government that had gotten out of control. While Baker seemed confident that he got the best of these exchanges, it’s clear that some readers found themselves nodding along with at least some of Benjamin’s ideas.

[Portland] Oregon Journal, April 6, 1963

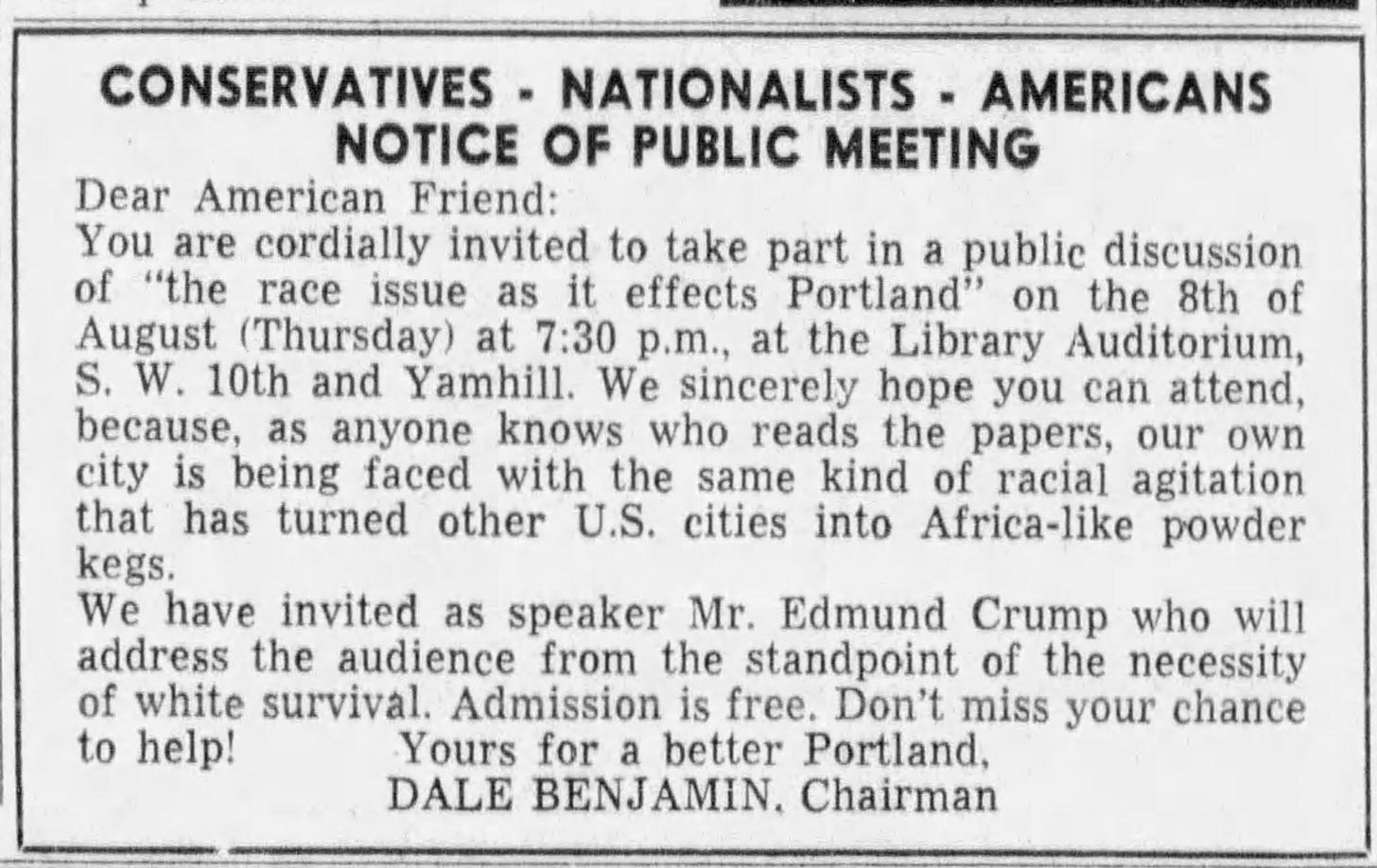

A few months after the above 1963 exchange with Baker, Dale Benjamin took out an ad in the paper inviting “conservatives, nationalists, and Americans” to attend a meeting at the main Portland library at which a local high school student would talk about the imperative of “white survival.” That high school student lived only a few blocks from Dale Benjamin in a working class section of far SE Portland, perhaps explaining how they came to know one another.

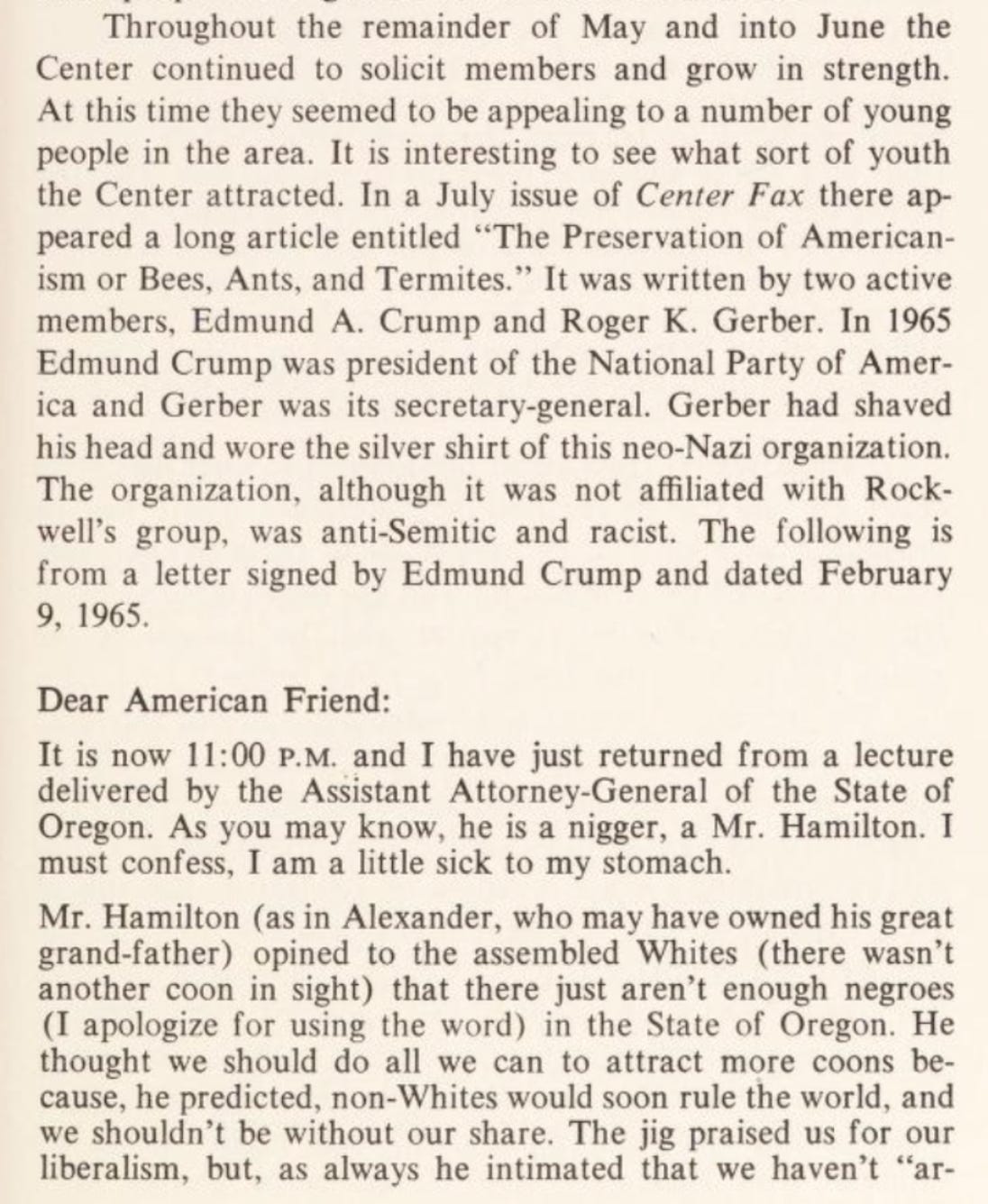

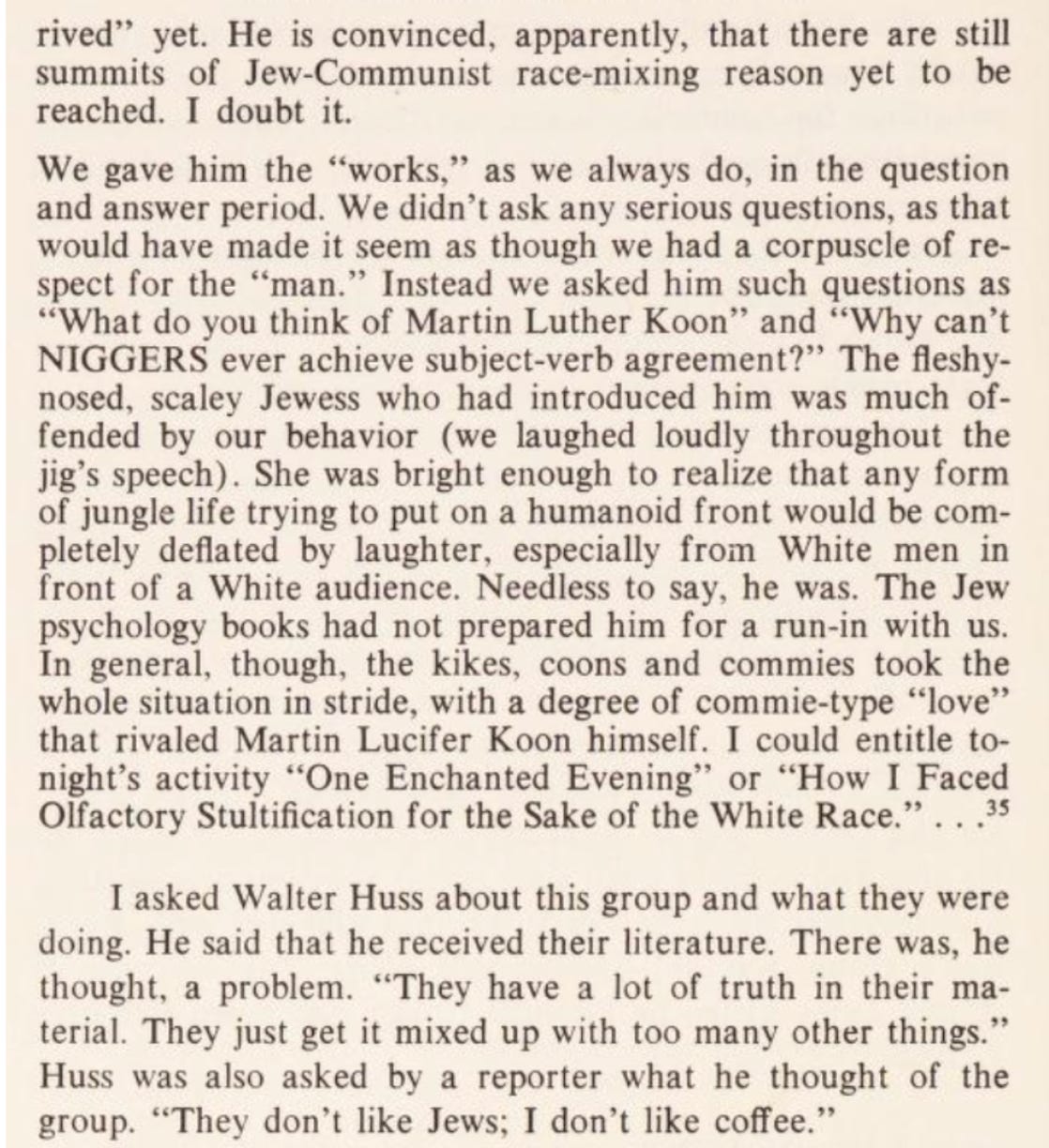

Another possible place that the 66 year old Benjamin could have met the teenaged Crump was at Walter Huss’s Freedom Center (also in SE Portland). Crump had published an article in Huss’s newsletter in 1961 and frequently attended meetings there until he formed his own group that was a few clicks to the right of Huss’s. The account below is from Scott McNall’s book on Huss published in 1975.

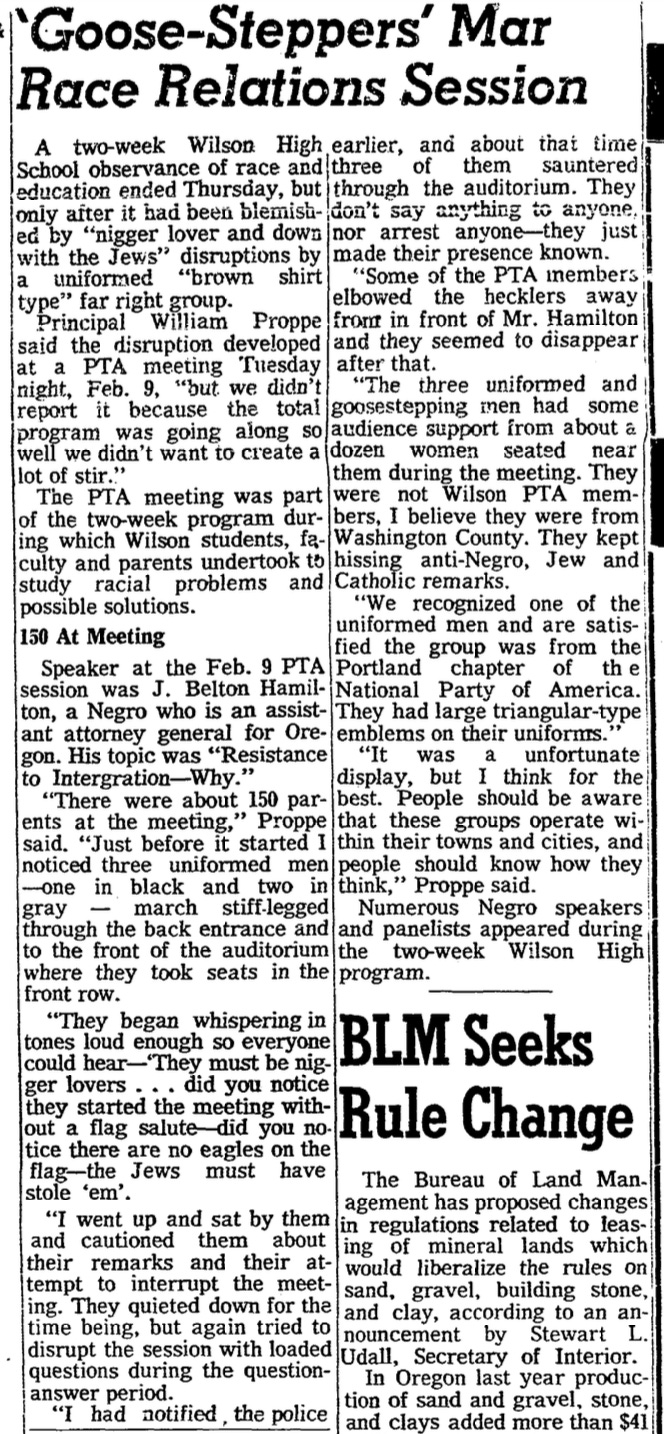

Those two young proteges (or at least associates) of Huss and Benjamin’s disrupted numerous public events in Portland in 1965 with virulently racist and antisemitic signs and chants. In one case they goose-stepped, in full silver-shirted regalia, into a PTA meeting about racism in Portland’s schools and sat in the front row hissing racist and antisemitic epithets at the panelists.

The Oregonian, February 21, 1965

After this flurry of activity in 1965, those two young men vanish from the archive and seem to have ceased their political activities. What I want to emphasize, however, is the multi-generational nature of Portland’s far right in the early 1960s. Benjamin was old enough to be Huss’s father, and Huss was old enough to be the father of those two goose stepping silver shirts who were egged on at that PTA meeting by a greek chorus of “a dozen [presumably older] women seated near them.” Benjamin had been an active participant in the terroristic activities of the KKK in the 1920s, and his young proteges described themselves as the heirs of William Dudley Pelley’s “Silver Shirt” movement from the 1930s. Benjamin’s story helps us see the throughline from the KKK to the Birchite far right of the 1960s and on toward today.

The direct actions these far right activists engaged in were not intended to change hearts and minds. Rather, they sought to creating a climate of terror that would intimidate white moderates into silence at a time when the civil rights movement was striving to win over the hearts and minds of those same moderates. We can see contemporary echoes of these sorts of far right direct actions in the multi-generational groups that have terrorized events like Pride parades and drag queen story hours. As with that 1965 direct action at the Portland PTA, the protesters include uniformed right wing thugs alongside middle-class “housewives,” both claiming to be defending children and “western civilization” from “radical left cultural degeneracy.” Just as a relatively small number of Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer members menaced Portland in the summer of 2018 creating a climate of terror and dread, Dale Benjamin and his young associates shaped the tenor of Portland’s public life in the 1960s far in excess of their relatively small numbers.

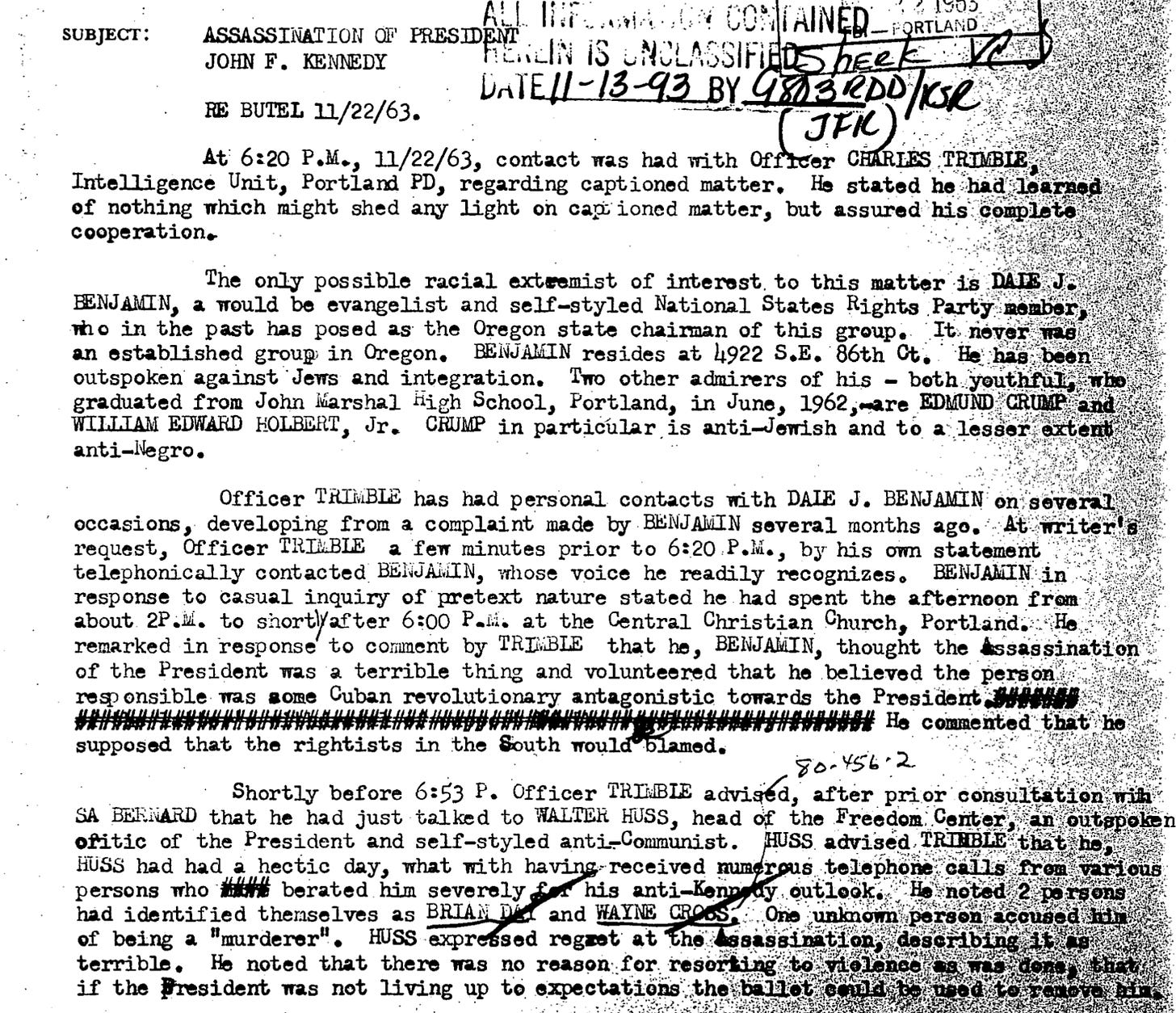

Let’s wind the clock back now to November 22, 1963, the day after Huss and Benjamin showed up at that bureaucratic meeting at city hall to troll the NAACP. Immediately following JFK’s assassination the FBI began contacting local field offices and police departments to see how the far right forces in their towns were responding, As we see in this police report below, the first people the authorities checked up on in Portland were Dale Benjamin, Walter Huss, and their young associate Crump.

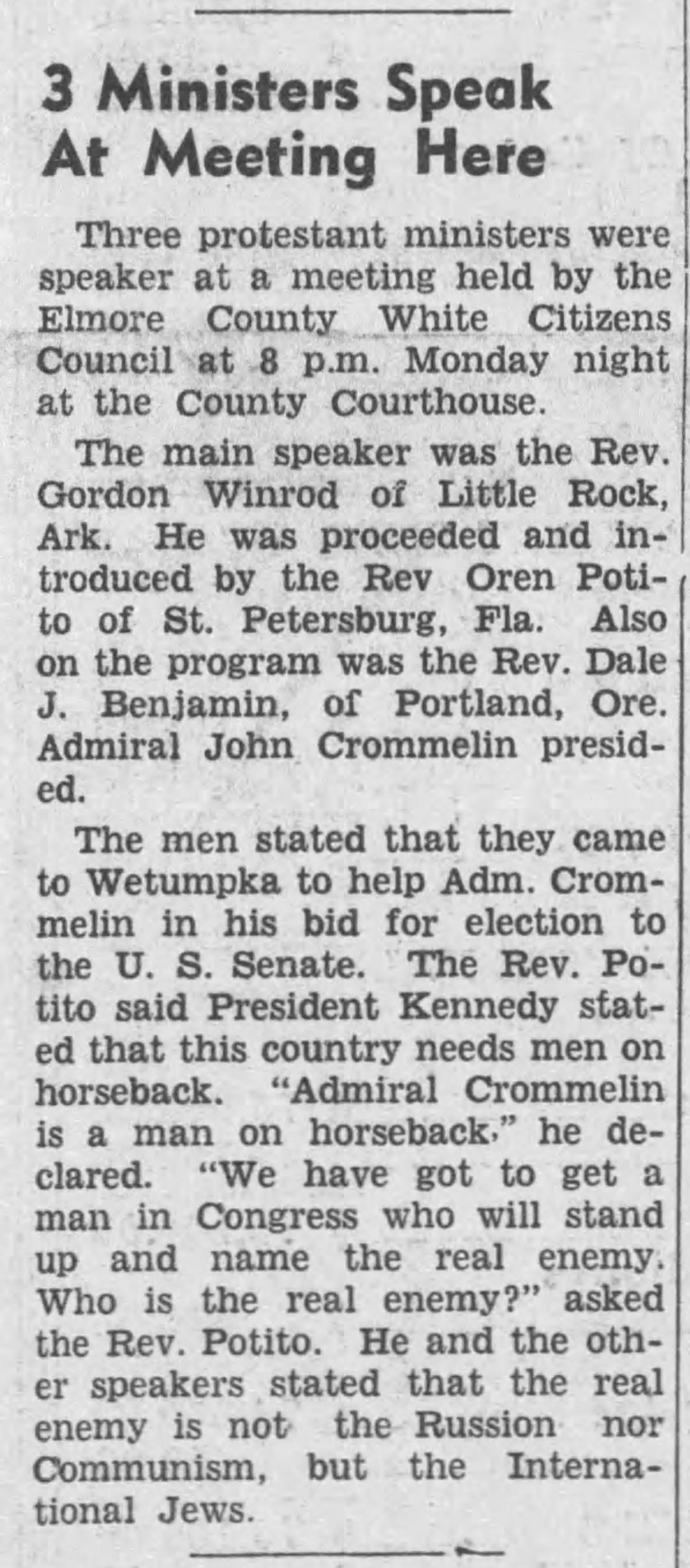

The FBI likely knew that Benjamin was networked in with some of the nation’s leading white supremacists who were known to engage in acts of domestic terrorism. Below we see Benjamin in 1962 traveling to Alabama to lend his name to the Senate run of one of the nation’s more notorious white supremacists and antisemites, retired Admiral John Crommelin. According to historian Clive Webb, the author of Rabble Rousers: The American Far Right in the Civil Rights Era, Crommelin’s “tireless networking…did more than any other activist of his time…to unify the fractious far right.” One of Benjamin’s fellow speakers at the event was Gordon Winrod, the son of Gerald Winrod, a Christian Nationalist preacher colloquially known as “the Jayhawk Nazi.” Columnist Doug Baker may have regarded Dale Benjamin as a pathetic local crank, but in the small but well-networked world of the American far right, Benjamin was rubbing shoulders with some of the most well-known and highly regarded “patriots.”

Wetumpka [AL] Herald, April 26, 1962

When Dale Benjamin died at the age of 70 in 1967 it merited a relatively long announcement in the Oregon Journal. While he was perceived as an ultra-conservative kook by most of his contemporaries, let’s pause to enumerate some of the causes he championed in the 60s that were considered kooky: abolishing the IRS (16th Amendment), ending birthright citizenship (14th Amendment), withdrawing from the UN, no federal aid to schools, putting prayer and the Bible back into public schools, banning pornography, draconian drug laws, and “right to work” (i.e., anti-union) laws. In the 1960s most of those positions were advocated by very few people in positions of power and authority in either party, whereas today such stances would put someone squarely inside the boundaries of the MAGA-fied GOP. In the eyes of many of his liberal and moderate contemporaries, Benjamin looked like an eccentric and relatively harmless throw back. Little did they know that in many ways his politics were the future of the GOP, in terms of the extreme policy positions he held but also in terms of his pugilistic political style that enabled him to pose as a menacingly angry “real American” AND a poor put upon victim of the nation’s “establishment.”

Oregon Journal, January 24, 1967

Every work of history has to at least implicitly have an answer to the question of “why the hell should we remember this part of our collective past?” I wish we could relegate figures like Dale Benjamin to the dustbin of history, and hopefully at some point we will be able to do so. But I’ve tried to make the case here that Benjamin, like Huss, played a historically significant role as what historian Elizabeth Gillespie McRae has called a “constant gardener” of white Christian supremacy. By treating Benjamin as a vestigial kook rather than as a dangerous inspirer and organizer of violent anti-democratic hatred, the Portland press both gave Benjamin a public platform for his ideas AND used him as a foil to convince themselves that American bigotry only manifested in outlandish figures like Benjamin who would soon enough take American-style racism and antisemitism to the grave with them. In hindsight, we now know that this did not happen. Hopefully Benjamin’s story, which resonates so powerfully with features of our contemporary politics, can help us understand a little better our present moment and how those of us who care about democracy are called to act in it.

It really is shocking to see how little has changed in the right wing litany of complaints and claims of victimization. Other than a few more blatant racist and antisemitic slurs, those letters could have been written today. I was a bit shocked that Baker cited a full street address in his response, though-- that definitely wouldn’t happen now. As you point out, it’s easy to see the baton of nationalism, racism, antisemitism and authoritarianism being passed along generation to generation.