How to Not See

Or, why Mark Hatfield memory-holed that time in 1962 when a Walter Huss-led protest at his house scared the crap out of his wife and young children

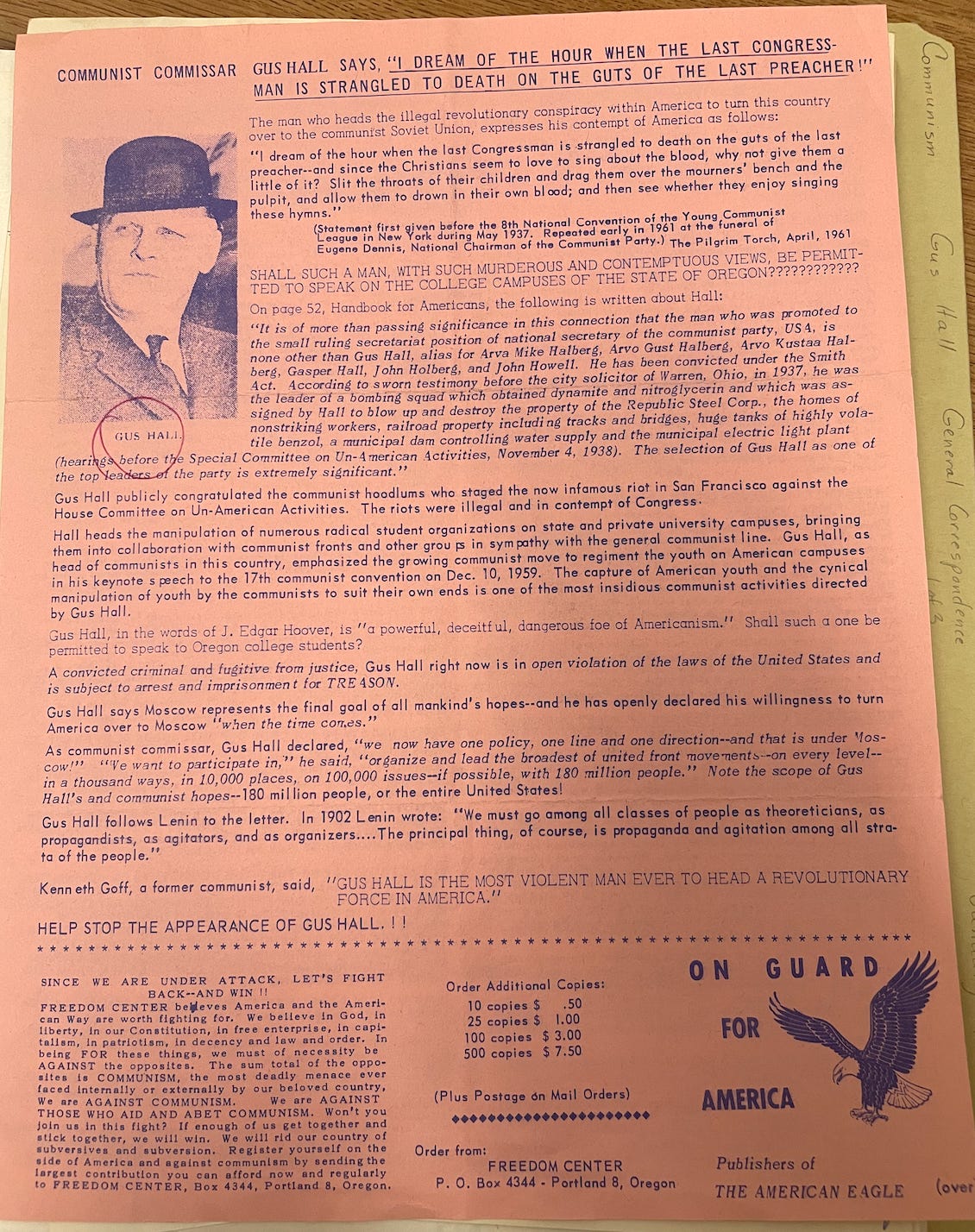

When the news came out that Gus Hall, the leader of the Communist Party in the US, was going to be speaking on multiple Oregon campuses in February 1962, Oregon’s leading anti-communist crusader Walter Huss snapped into action. He printed and disseminated a flier letting folks know why Gus Hall (real name Avra Gus Halberg, wink wink) posed an existential threat to the state and must be forbidden from speaking. Huss’s flier opened with a salacious and fake quote from Hall. Huss always had an eye for the arresting propagandistic line. And he was never overly concerned about the veracity of his claims. [Interestingly, that fake Gus Hall quote was still being repeated twenty years later in the 1980s by Jerry Falwell and appeared in a draft of a Reagan speech but was taken out at the last minute.]

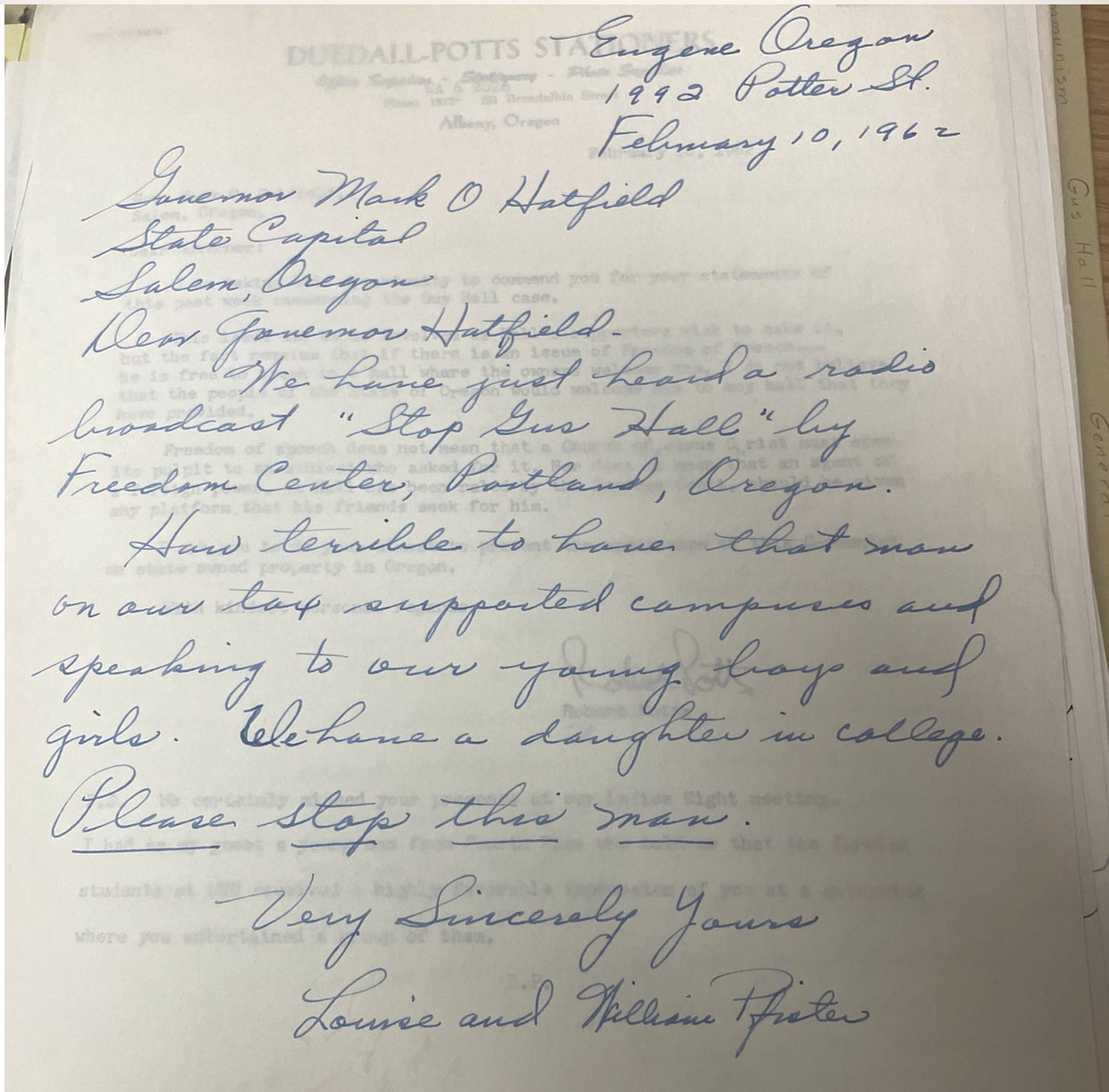

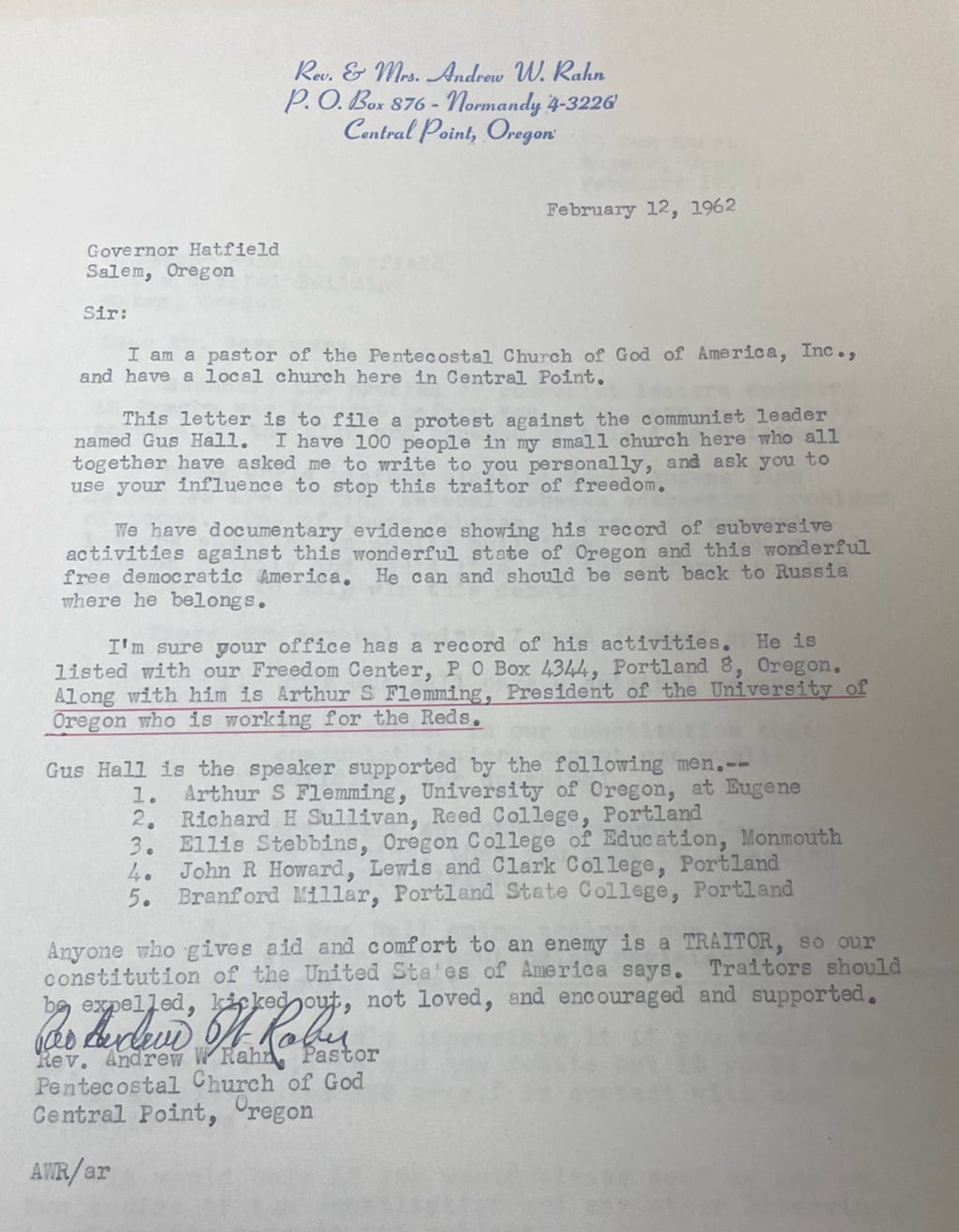

Huss also spread the word about his “Stop Gus Hall” campaign on his daily radio show which was broadcast on several AM stations across the state. In the week of February 7-14, 1962 Governor Mark Hatfield received over 125 individual letters or telegrams (several signed by long lists of people) imploring him to stop Gus Hall from speaking in the state of Oregon. Dozens of these letters and telegrams specifically mentioned that Walter Huss had inspired them to write, and many more of them (the majority, I’d say) contain quite specific and often identical references that strongly suggest that Huss was the main source of their information about Hall.

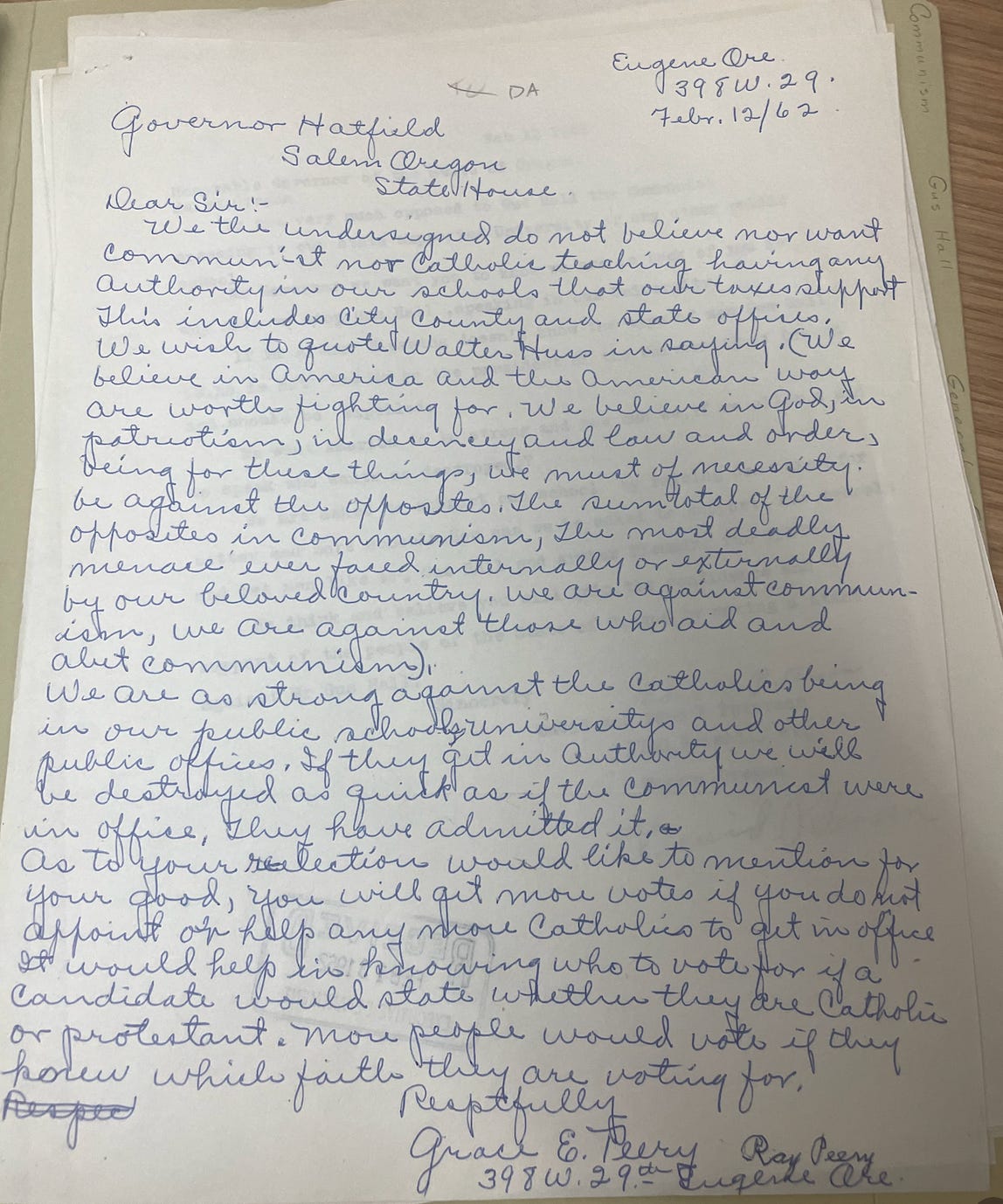

Below are two representative samples of the letters Hatfield received that mention Walter Huss’s “Freedom Center.”

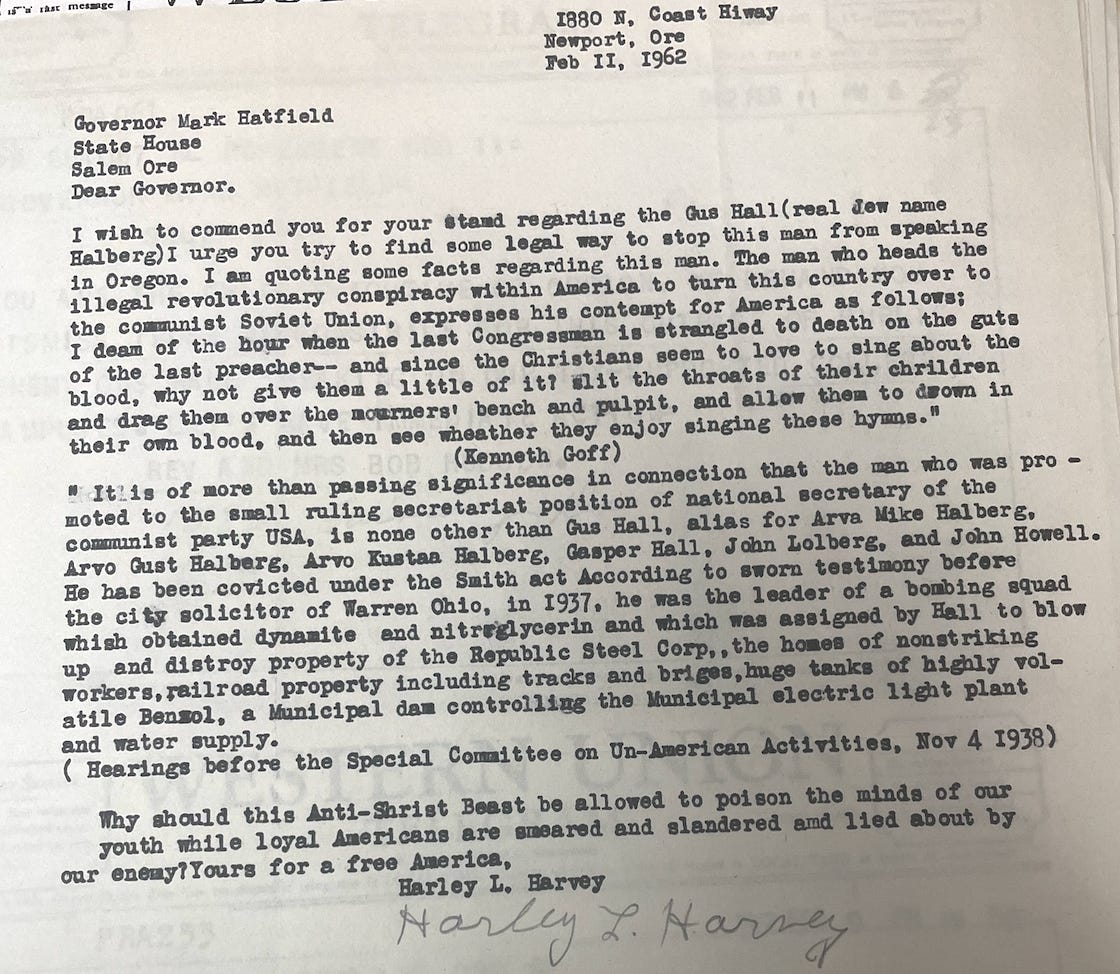

A few of the letters to Hatfield extrapolated from the information in Huss’s flier to draw out the more explicitly bigoted implications of Huss’s world view. The letter below, for example, picked up on Huss’s winking reference to Gus Hall’s “real Jew name Halberg.” [Note also this person’s reference to Kenneth Goff, who Huss had also cited in his flier. Goff was a white supremacist and antisemite who was involved with a violent far right paramilitary organization called The Minutemen. He also was the person responsible for fabricating that salacious quote from Hall that Huss put in all caps on the top of his flier. In the fall of 1963 Huss took Goff on a week-long speaking tour throughout the Pacific Northwest. More on that in a future edition of Rightlandia.]

The letter below is noteworthy in that the writers expressed as much concern about Catholics as they did about Communists, a relatively old-fashioned form of bigotry in 1962. The second KKK of the 1920s flourished in Oregon where it took on a predominantly anti-Catholic tone. As I note in this previous post about another of Huss’s compatriots, there were many genealogical ties that linked the Oregonian far right of the 1960s to the KKK of the 1920s and the Silver Shirts of the 1930s. While I’ve seen no indication of anti-Catholic sentiment in Huss’s papers, it’s interesting that these admirers of his connected their fears about the Communist menace to their fears of the Catholic menace, both of which (in their minds) did their evil work by secretly taking over public institutions and then using their power to oppress upstanding “Christian patriots” like them.

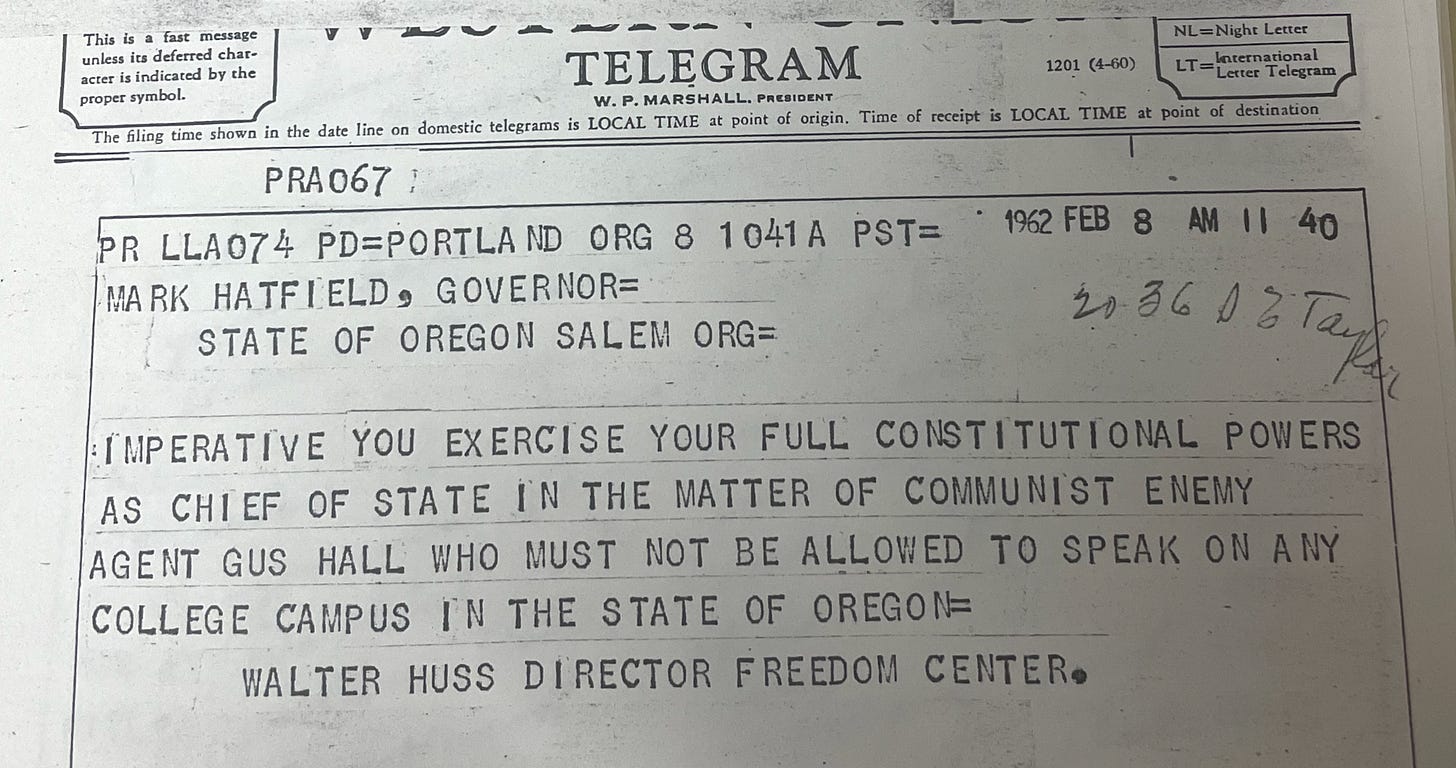

The above letters from Newport, Central Point, and Eugene are indicative of how Huss-inspired correspondence poured into the Governor’s office from all over the state. This letter-writing campaign took place only two years after Huss had set up shop at his Freedom Center in Portland, testifying to Huss’s organizational efforts. By early 1962 he had enough people in his radio audience and on his mailing list that he could get hundreds of Oregonians from across the state to flood the Governor’s office with individually-written telegrams and letters in the space of a few days. Huss weighed in with a terse but direct telegram of his own to the Governor.

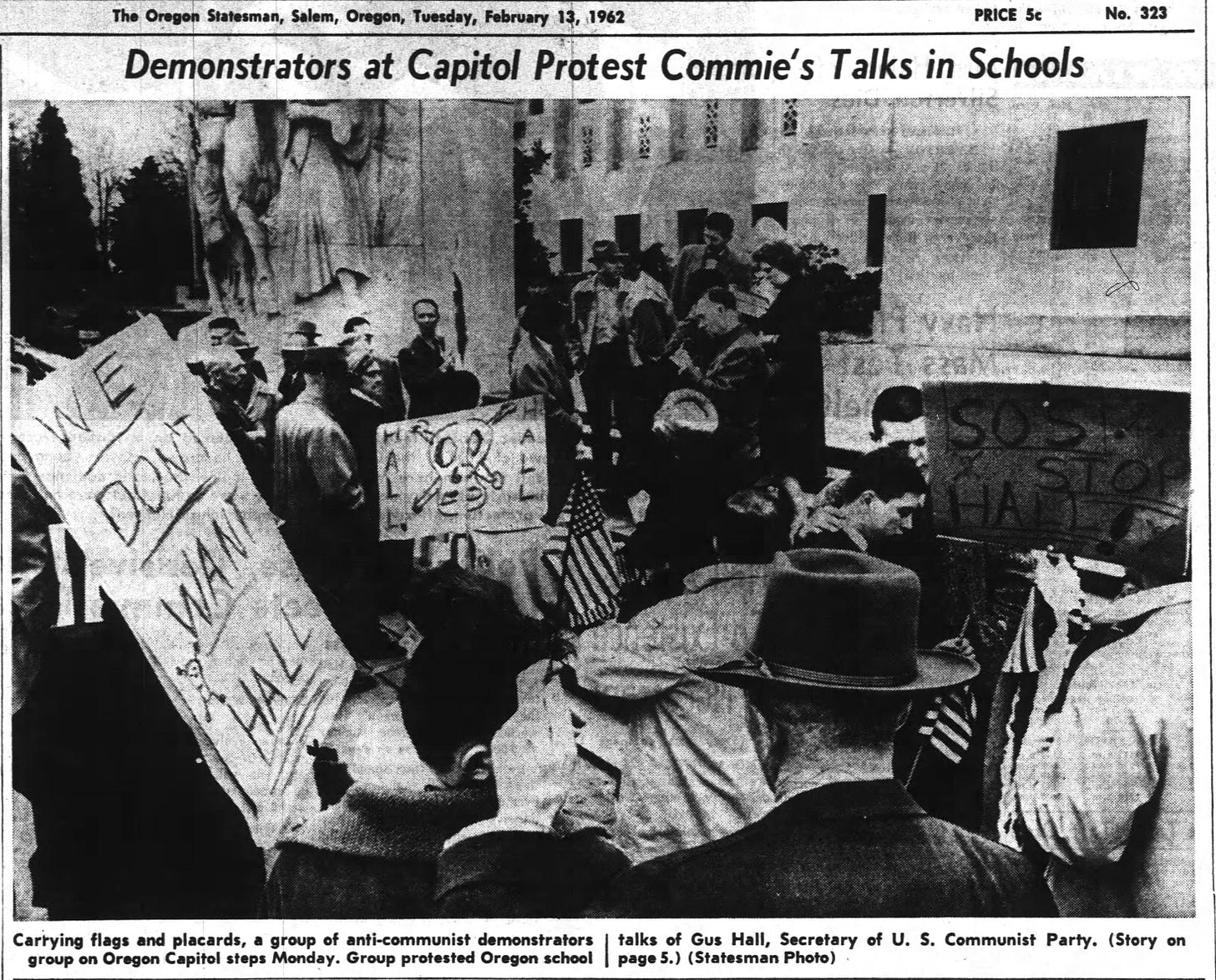

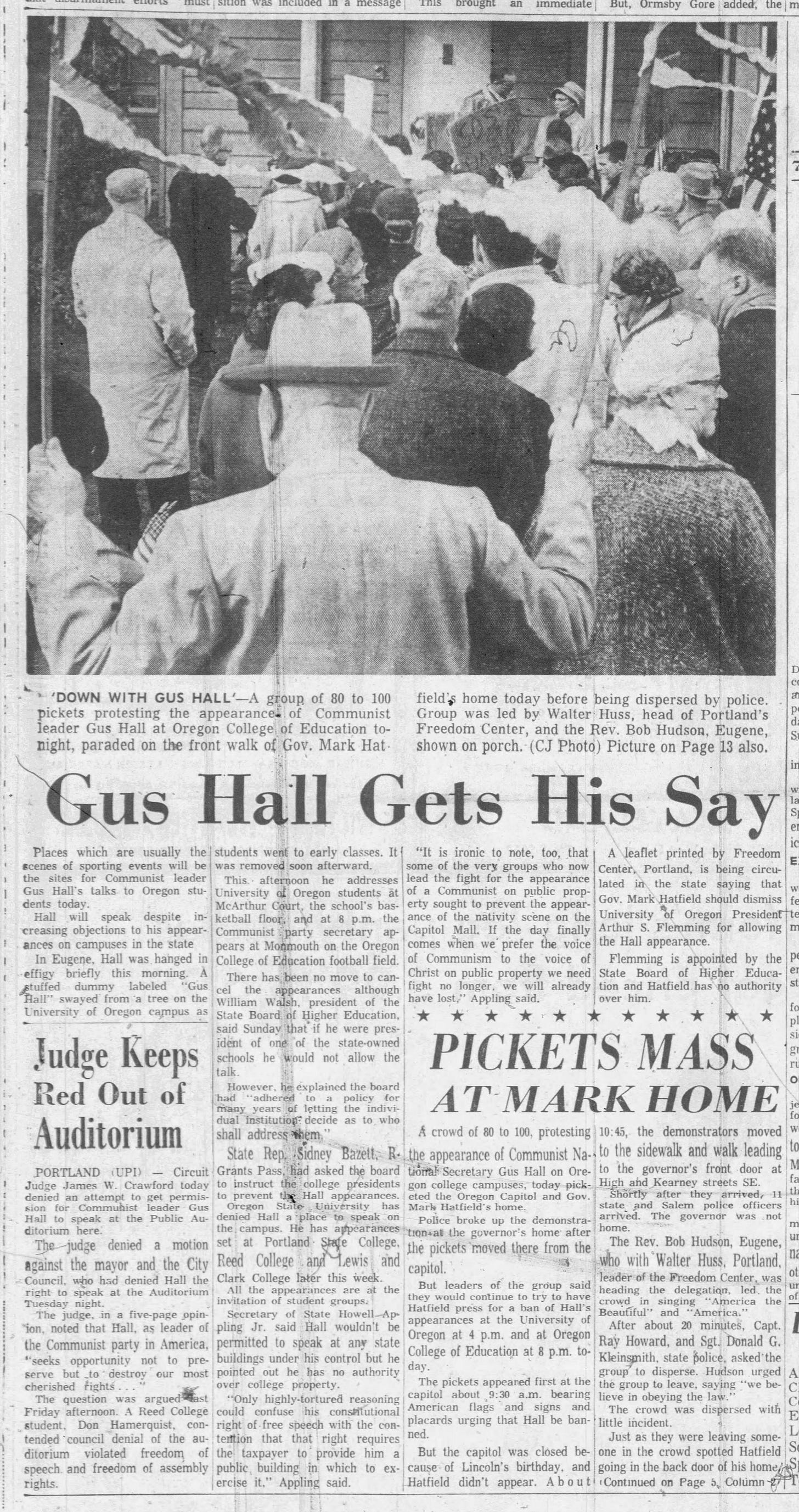

But Huss was not content to barrage the Governor with letters and telegrams. On February 12 he organized a group of 80-100 people from around the state to go to the capitol building in Salem to press their case in person with the Governor. [Walter Huss is the guy in the bow tie near the top of the photo.]

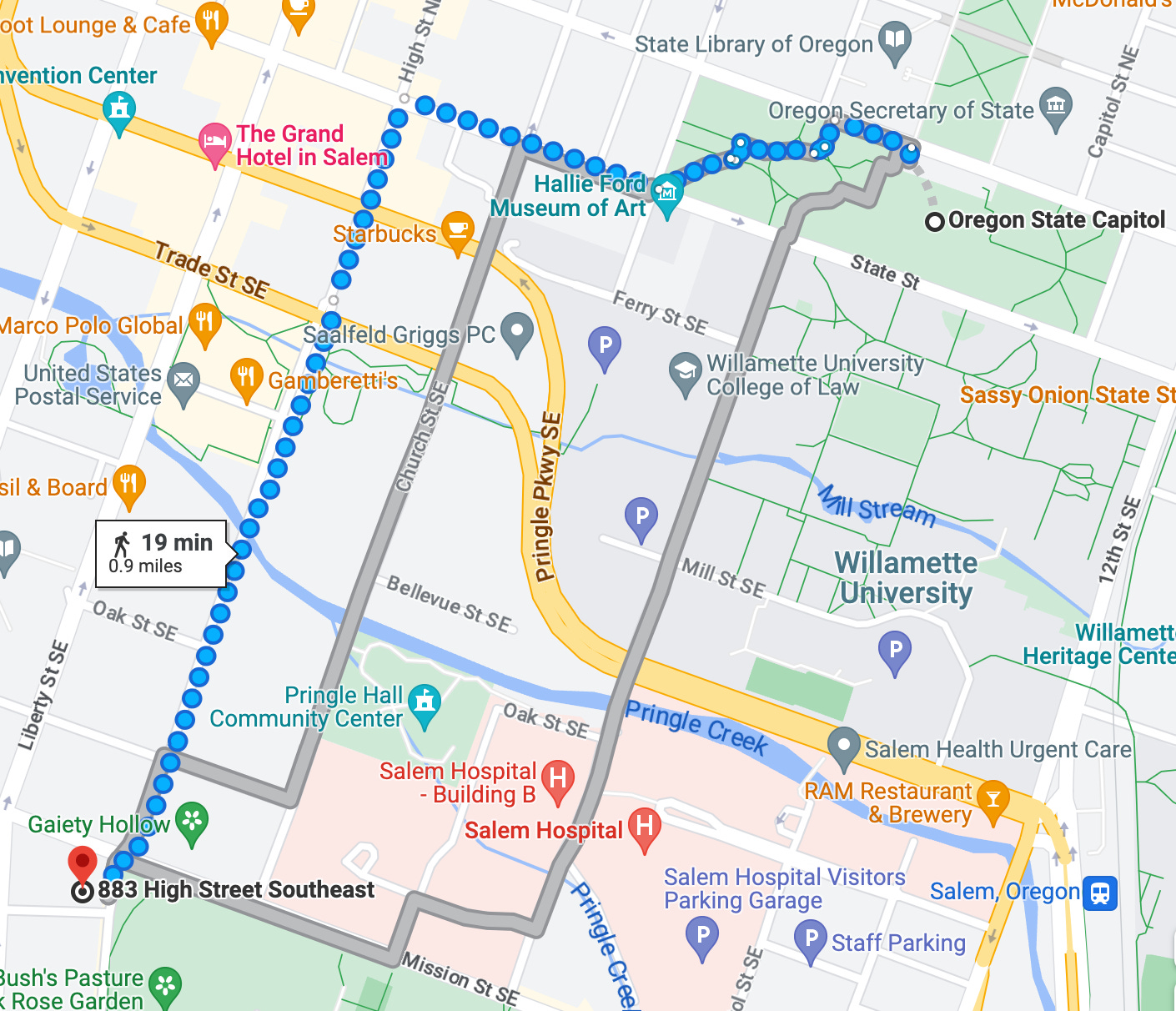

Because it was Lincoln’s Birthday, however, the building was closed and the Governor was not at his office, so Huss led his group on a one mile walk to the Governor’s home at 883 High St.

Around 10 o’clock in the morning Antoinette Hatfield was in her house alone with her two young children when she heard an unexpected ring of the doorbell and a pounding on the door. She looked out the window to see a large crowd of picket carrying protesters standing on her front lawn. The crowd quietly dispersed after the police arrived (perhaps called by Mrs. Hatfield, though the Governor denied this), but the Governor and his wife were clearly perturbed by this unannounced and unprecedented protest at their private residence.

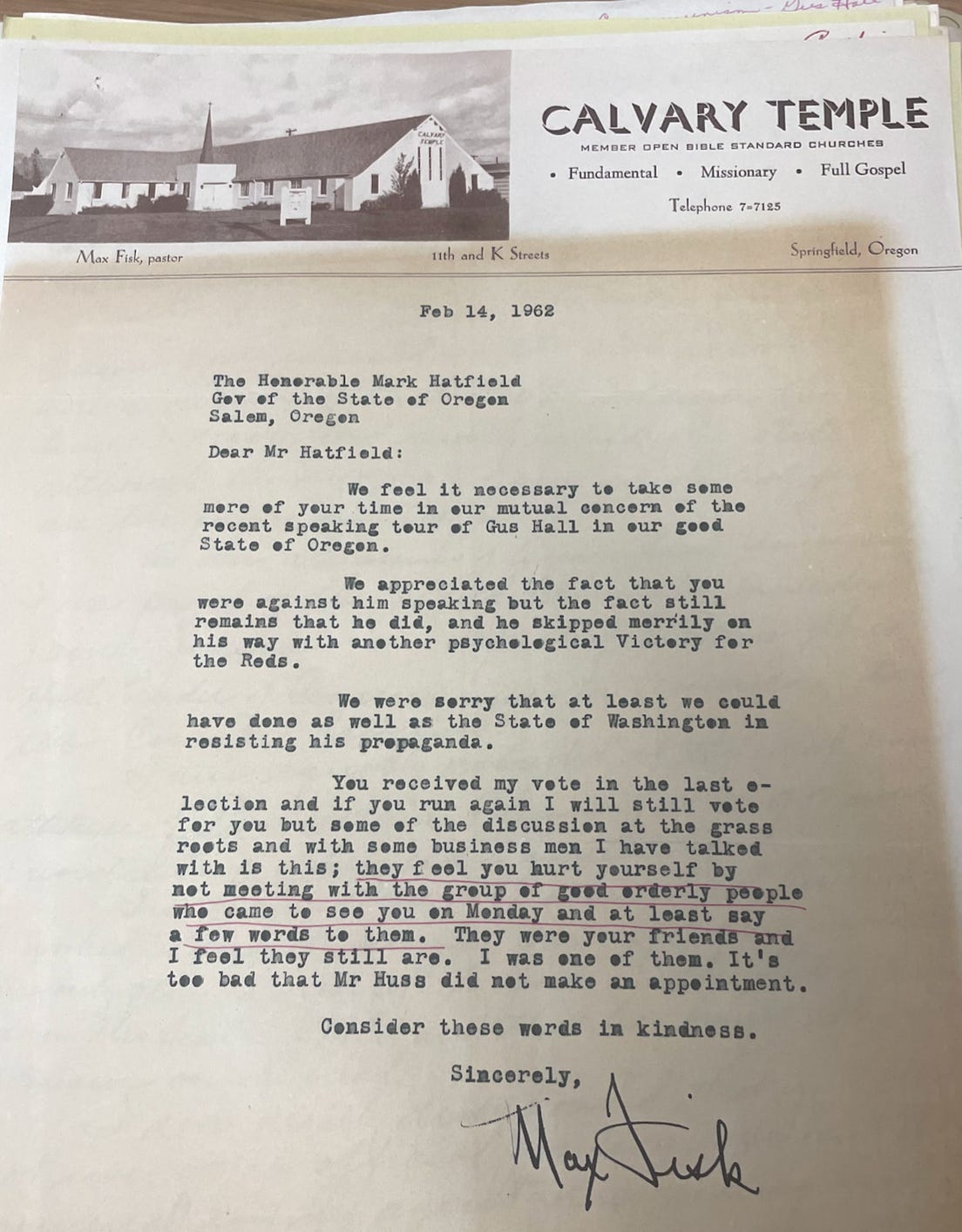

As this letter below from one of the ministers who participated in this direct action shows, these protestors thought of themselves as part of a growing grassroots insurgency that was being ignored by establishment politicians like Hatfield. Huss would deploy such populist anti-communist rhetoric for the entirety of his 40-year political career in Oregon. The insinuation was that something fishy must be afoot when a Governor would stand back and let a Communist talk at the University of Oregon, while refusing to meet with a group of Christian anti-Communists who’d simply knocked on his door.

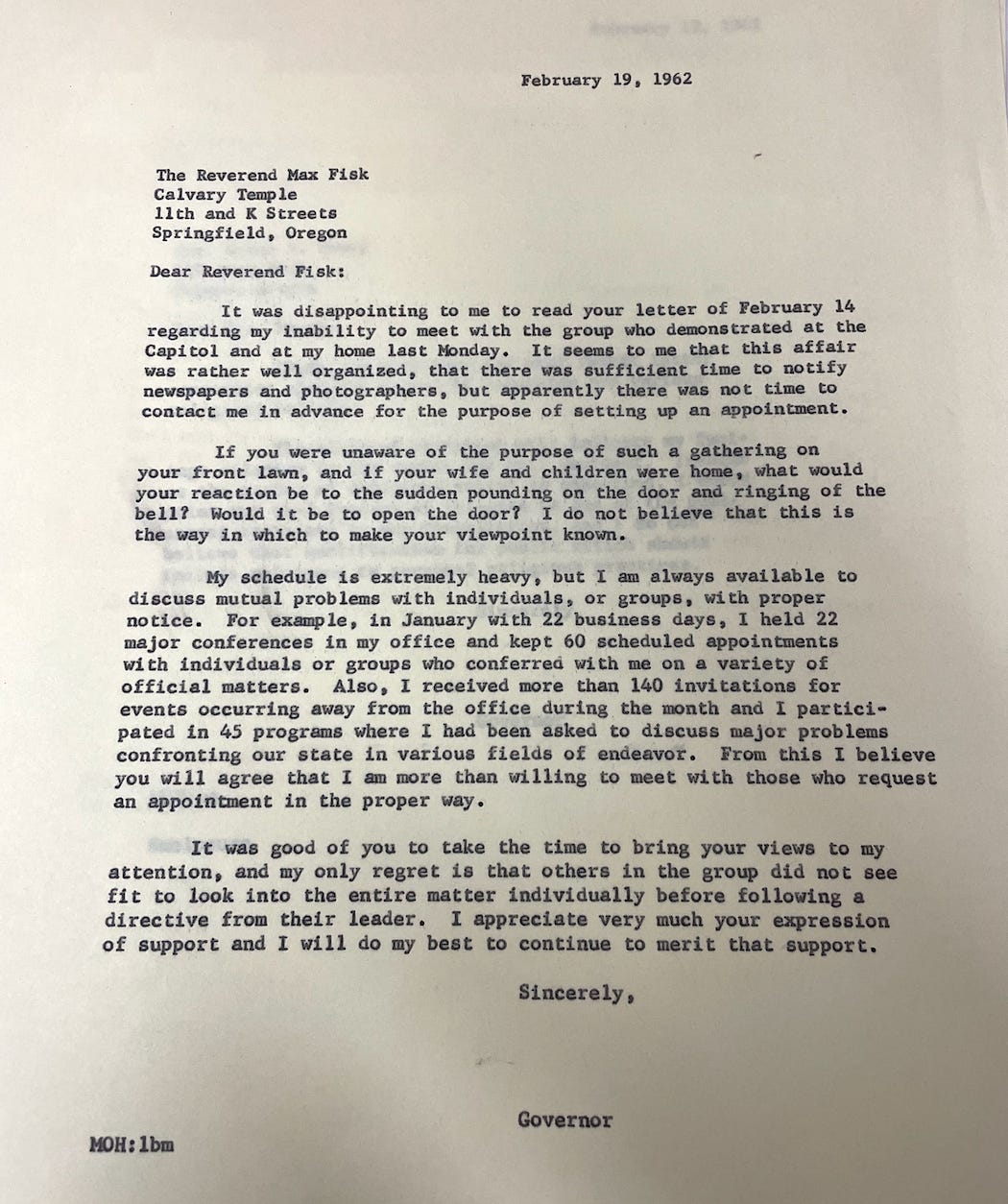

In his reply to Rev. Fisk, Hatfield made clear his displeasure with what to him looked like the disorderly and inappropriate methods deployed by Huss. To Hatfield this felt like a publicity stunt orchestrated by an aspiring authoritarian leader, not an effort at good faith political engagement.

In sum, what this episode shows us about Walter Huss is that in the span of two years and with virtually no money he’d built a state-wide grassroots organization capable of quickly mobilizing hundreds of people for direct actions and letter-writing campaigns that drove a lot of press coverage and attention his way. At this point in my research I’ve been able to identify several grassroots activists in counties across Oregon who were in Huss’s network from the 1960s into the 1990s. Over those 40 years they contributed small amounts of money, organized local talks, ran for GOP precinct captain, wrote letters to the editor or elected officials, attended school board meetings, circulated petitions, made fundraising phone calls, shared recommendations for “patriotic” far right reading material with their neighbors, spread the word about the latest far right outrage du jour in their churches, and so on. This was the daily, quotidian stuff of which the long game of the grassroots far right insurgency was made. And all of it flew almost entirely under the radar of Oregon’s moderate Republicans like Mark Hatfield and Bob Packwood.

Although Hatfield had no way of knowing it at the time, that direct action at his house in 1962 was the opening salvo in what would become a three-decade war of harassment that Huss waged against Hatfield. In 1966 Huss ran against Hatfield in the GOP primary for US Senate. Hatfield wouldn’t give this annoying extremist the time of day, so Huss followed him around the state peppering him with questions from the audience. Twelve years later, in September 1978 after Huss had taken over as chair of the Oregon GOP and when Hatfield was running for reelection, some of Huss’s associates posted signs at the official GOP booth at the Jackson County fair that labeled Hatfield a “traitor.” [Huss received a fiery letter from the national RNC chair upbraiding him for this breakdown in party discipline.] Huss’s elevation to OR GOP chair elicited a shocked article in the Washington Post in 1978 asking what the hell was happening in Oregon, and even Gerald Ford inquired about “that nut” who had taken over the OR GOP. Huss’s takeover of the OR GOP, the culmination of his 16-year battle against establishment “pinkos” like Hatfield, was a pretty big deal.

But here’s the puzzling thing: Hatfield said almost nothing about Huss publicly, and in the 900 page oral history interview he conducted with the Oregon Historical Society in 1998 he mentions Walter Huss exactly once. The oral history reveals that not only did Hatfield forget that Huss was his 1966 primary opponent, he also mistakenly thought 1966 was the year Huss had become OR GOP chair, missing it by 12 years. That’s a pretty significant error and testifies to something I’ve heard from many Hatfield associates, which is that Huss taking over the OR GOP was fairly inconsequential for Hatfield because he didn’t need the state party to get elected and rarely had any interactions with it. I have no reason to doubt this explanation for Hatfield’s relative lack of interest in and memory of Huss, but that’s not the end of the story.

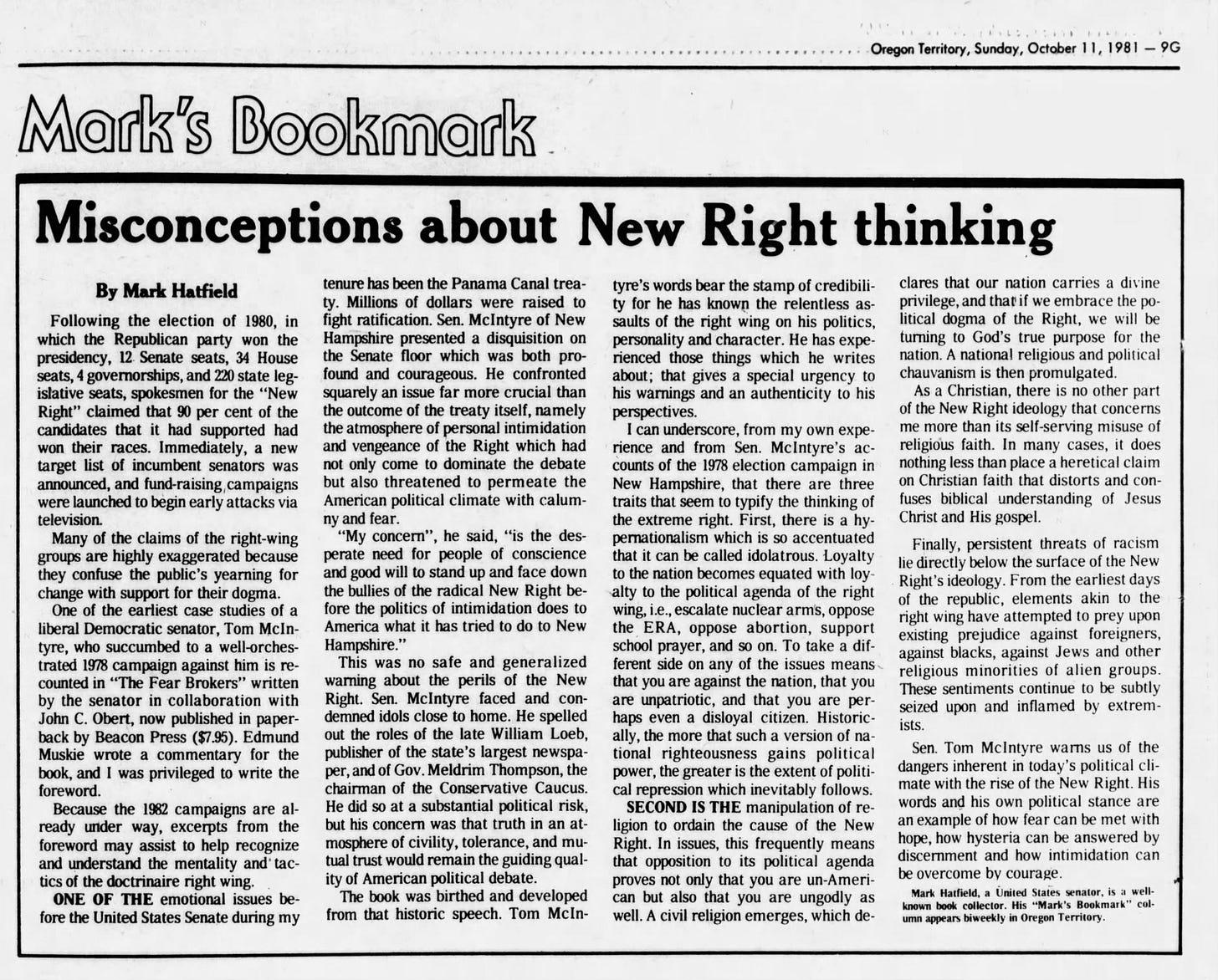

Hatfield’s disinterest in what Huss was up to is notable because Hatfield prided himself on being not just another pragmatic power politician, but on being a man of principle. And one of the principles Hatfield was most known for was his outspoken opposition to far right extremists like Huss. He’d called out the John Birch Society in his 1964 GOP convention speech and he’d written the forward to a 1968 book that offered a critical look at Billy James Hargis and the evangelical far right. Where most of Hatfield’s Republican colleagues chose to remain expediently quiet on the rising power of the far right in their party, Hatfield made speaking out about the danger of the right wing an important part of his political brand into the Reagan era even though he received significant blowback from other Republicans.

So it’s a genuine puzzle (that I’m still trying to figure out) as to why Hatfield, longstanding and outspoken critic of the far right, seems to have done almost nothing to push back against Huss’s long-running and precociously successful far right insurgency inside the Republican party IN HATFIELD’S HOME STATE. Likewise, in 1998 when Hatfield sat down for this oral history interview, one of his significant concerns at the time was the way moderates like him had been driven out of the Republican party both nationwide and in Oregon. In the late 1990s a group of moderate former Republican officials and staffers met regularly for breakfast in Salem where conversation would sometimes turn to lamentations about the current sad state of the increasingly far right OR GOP. From what I can tell, it did not occur to these folks to pin any of the blame on Walter Huss, one of the people who was arguably most responsible for building the grassroots far right insurgency that gradually pulled the party out from under the feet of those moderates.

I think we can solve this puzzle by looking at how Hatfield defined and understood “the far right.” He understood it as a malign spirit, as a pathological mindset akin to historian Richard Hofstadter’s “paranoid style.” Hatfield didn’t see the far right as a rival political organization that in many ways resembled his own—one that had mailing lists and phone trees, and which staged public meetings, raised funds, recruited and promoted specific candidates for office, had influential point people in every county in the state, and so on. Regarding Huss as a pathological kook made it unlikely that Hatfield would ever accurately perceive (and then effectively counter) the grassroots mobilization Huss inspired.

The growing organizational and institutional coherence and power of the grassroots far right inside the GOP is of course far easier to see in hindsight than it was at the time. When I spoke last month with Scott McNall, the author of a 1965 dissertation and then a 1975 book on Huss subtitled “A Study in Failure,” he told me that it seemed inconceivable to him in the 1960s that Huss’s variety of politics would have a viable future. One motivating question driving my research is this: “why did otherwise perceptive people not see that Huss’s 1960s and 70s politics was far more in line with where the OR GOP was headed than the more moderate politics of well-known public figures like Hatfield, Bob Packwood, or Tom McCall?” I hope that getting some greater clarity on that question can help us do a better job of understanding and acting within our current political situation which, though different in many ways, rings with the echoes of these earlier iterations of far right insurgency.

To return to (and end with) Gus Hall, here’s how Hatfield remembered that 1962 incident in his 1998 oral history.

It’s unsurprising but notable that Hatfield did not remember that Huss was the organizer of this action. Hatfield remembers the Gus Hall kerfuffle as a silly controversy whipped up by “the media,” as if those protesters spontaneously showed up to harass his family on their own initiative. But I’d argue that “the media” wasn’t the sole or even primary mover behind this controversy. Rather, it was Huss who mobilized that crowd at the capitol and the Governor’s house, and who inspired hundreds of people to send letters to the editor and to officials like Hatfield. Hatfield had to deal with this situation, in part, because Huss mobilized the grassroots far right so as to create enough pressure to force Hatfield to deal with it. Huss, in other words, successfully drove the agenda of what people in the state were talking about in early February of 1962, even if he ultimately failed to prevent Gus Hall from speaking.

Mark Hatfield measured success in elections won and policies passed and successfully implemented. By that measure he was quite a successful political leader. And by that measure, Walter Huss was a laughingstock, a kook, a failure, a bit player in Oregon political history. But Huss measured success differently—in moral panics stimulated, grass roots cynicism stoked, liberals like Hatfield flummoxed (if only temporarily), and in the many close bonds he formed with his fellow far right Christian Nationalist activists around the state who vowed to keep fighting against the malign, conspiratorial forces they perpetually thought were on the verge of destroying American civilization. Huss skillfully stoked those reactionary fires for 40 years, doing his bit to cultivate an increasingly alienated and angry, populist, anti-government, illiberal “conservative” political culture that took root in the state’s rural areas and churches, and which would eventually become the OR GOP’s dominant culture.

I think the current tendency to view MAGA reps like Boebert, MTG, Gaetz, etc as targets for mockery rather than as serious opponents is a continuation of Hatfield’s attitude. It’s hard to take folks like that seriously, but when they have corrupted the Extreme Court, it’s past time to do so.