The Everyday Antifascists who pushed back against Walter Huss, Episode 1

Or, that time in 1963 when four high school students from Albany, OR exposed Walter Huss and his pal Ken Goff for the violent bigots they were

Writing one Rightlandia post after another about the worst people in the world gets exhausting after a while. So I’ve decided to spend more time writing about the everyday antifascists who pushed back against Walter Huss and the broader ultra-right insurgency of which he was a part—like I did in this piece about Homer Ayres (1899-1992), the antifascist rancher from Sturgis, SD. Today’s installment features a story that stretches from Eugene Debs to Thurgood Marshall to the nuclear freeze movement to Qanon and the Montana militia. And it all starts in 1963 with four high school students in Albany, OR who decided to show up and ask some tough questions at an event held by Walter Huss and his fascist friend Ken Goff. I tracked down one of those high school students on Facebook a few weeks ago and he generously spoke with me on zoom for 90 minutes. His story helped me situate that 1963 confrontation in a century-long history of American fascist mobilizations and democratic counter-mobilizations.

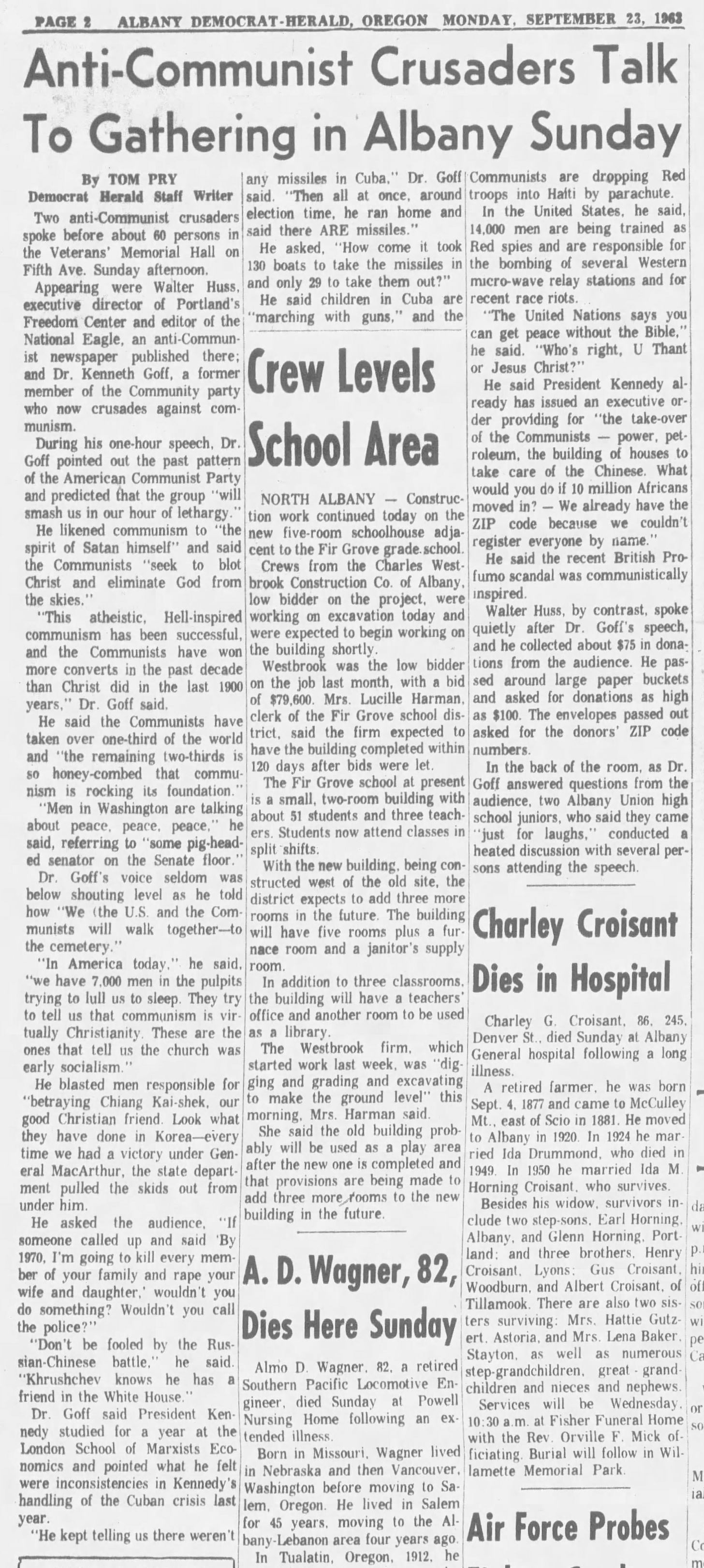

In 1963, Walter Huss took one of his heroes and fellow anti-Communist activist Kenneth Goff on an extended speaking tour around Oregon. Where Huss tended to mask his hateful racism, antisemitism, and apocalyptic fantasies about righteous political violence behind the smiling face and soft voice of an avuncular preacher, Goff was far angrier and more direct. I discussed Goff’s violent anti-democratic extremism in this post from a few months ago.

This 1963 story starts innocuously enough with Goff speaking to an audience of 60 people in Albany, a town of about 11,000 people located on the Willamette River 45 miles north of Eugene and 70 miles south of Portland. As you can see in the description below, Goff’s ranting speech overflowed with fascist hellfire and brimstone, warning the audience of a fast approaching future in which a pinko JFK would hand over “your wife and your daughter” to be raped by Satanic Communist marauders. One of the two unnamed high school students who attended “just for laughs” and got into a “heated” conversation with attendees at the event was David Belden, the person I interviewed a few weeks ago. Belden, like many on the left in the early 1960s, had developed an interest in the rising far right of his day. He visited local John Birch Society meetings in the summer of 1963 as a curious and critical observer, and that’s where he’d gotten wind of Goff and Huss’s upcoming visit to Albany.

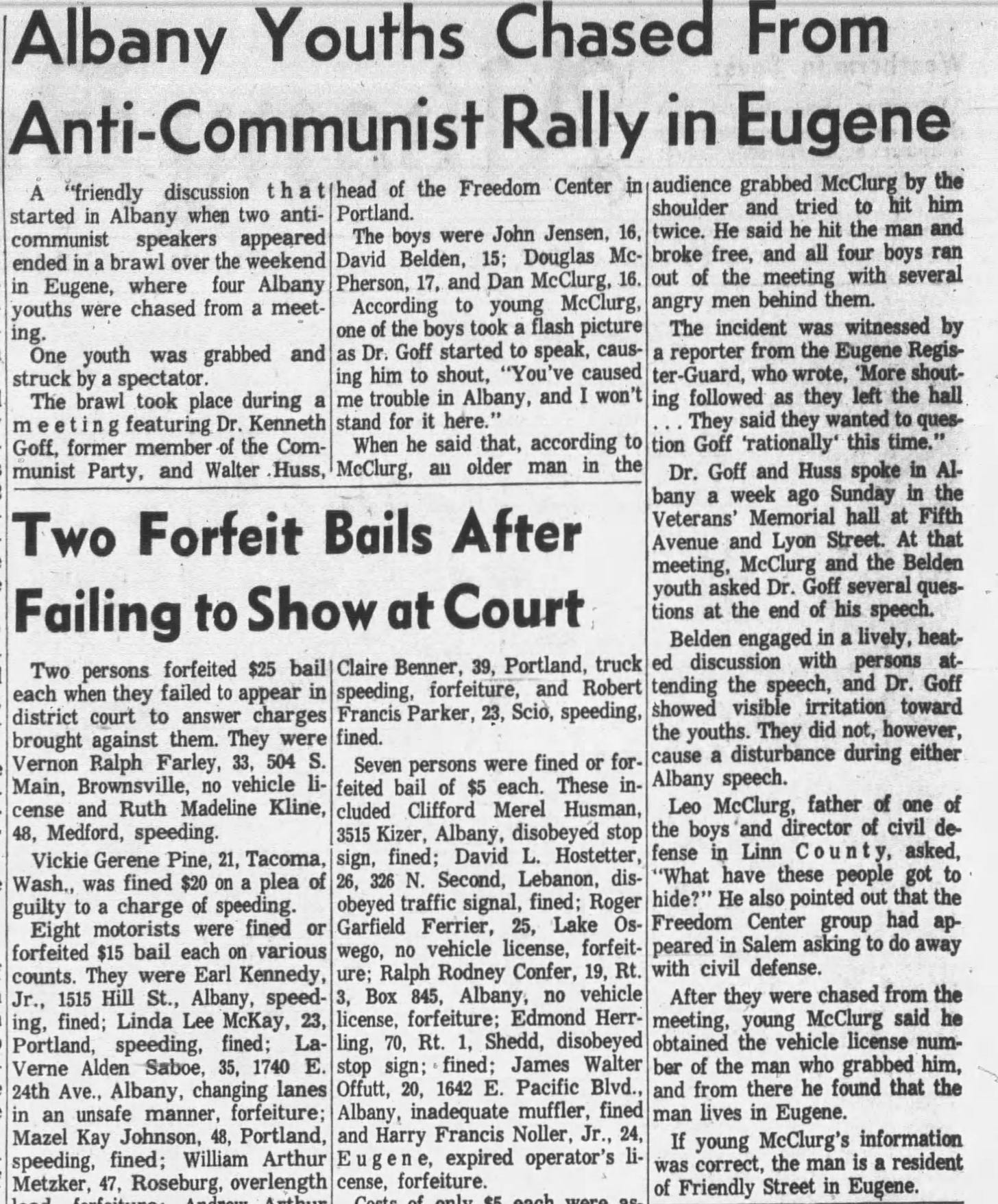

After his initial encounter with Goff in Albany, Belden and three friends decided to drive down to Eugene to witness the Commie-crushing superhero duo’s next event and to raise some more questions about the dubious veracity of Goff’s apocalyptic claims. That’s when things got more heated. About 20 minutes into Goff’s Eugene talk, one of Belden’s friends used a flash camera to take a picture. After a startled Goff yelled out in anger, a member of the audience jumped up, put Belden’s friend Dan McClurg in a headlock, hollered “this one’s mine!,” and began punching him in the head.

Albany Democrat-Herald, 2 October 1963.

This scuffle made its way into the newspaper because a reporter from the Eugene Register Guard had been assigned to report on this Goff event. That reporter followed the high schoolers out onto the sidewalk and got their names and their story. According to Belden, Goff’s presentations in Albany and Eugene were rife with antisemitic and racist comments, including the claim that the only thing that had ever come out of Africa was rock and roll, and that rock and roll musicians like that newly-famous band The Beatles were part of the communist conspiracy that used advanced psychological warfare tactics to brainwash America’s youth. Belden described the crowd as entirely white, almost entirely male, and filled with folks who felt quite alienated from contemporary American society, despite their sense that they were the “real Americans.”

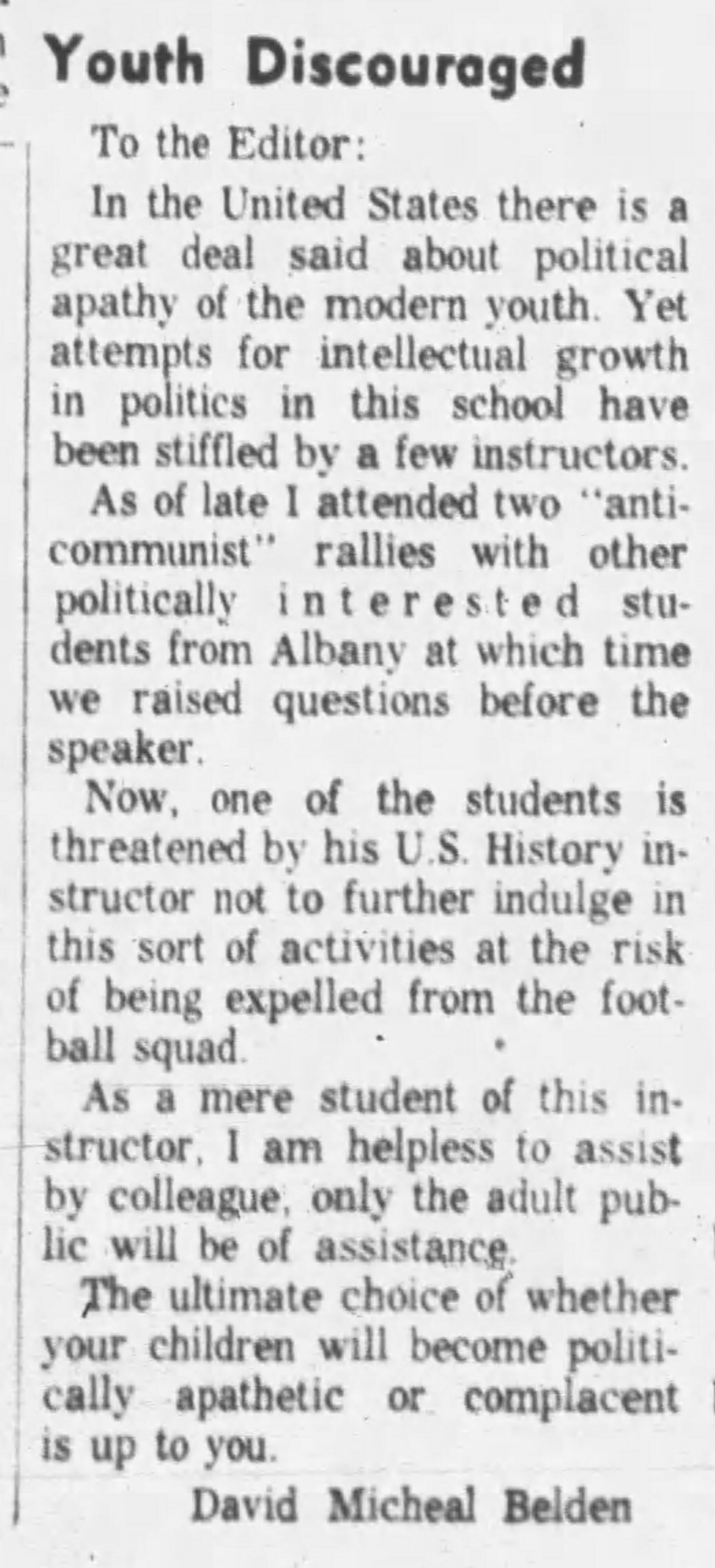

But the story doesn’t end with Belden and his friends getting jumped by a Eugene “Christian patriot.” The news about their experience created quite a stir back at Albany High. Dan McClurg, who played on the football team, was angrily told by his US History teacher (who was also his football coach) that he’d be permanently benched unless he promised to never do anything like that again. Belden was outraged on his friend’s behalf. A raving racist and antisemite came to town to gather recruits for his fascist cause and **we** are the bad guys because we peacefully raised some critical questions and were then assaulted for doing so? Belden wrote a letter to the editor exposing this behavior on the coach’s part, and he was then interviewed on KGW radio by the host of the most popular rush hour show in the state.

Albany Democrat-Herald, 5 October 1963

Belden’s protest and McClurg’s plight garnered much sympathetic attention in the Willamette Valley in October of 1963, but ultimately Belden’s lone voice was not of sufficient power to change things in Albany. Dan McClurg did not agree to his teacher/coach’s ultimatum, and he was permanently benched. The coach faced no repercussions for his actions.

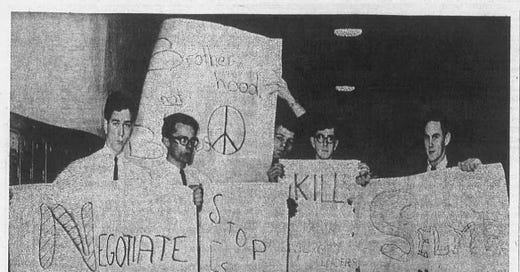

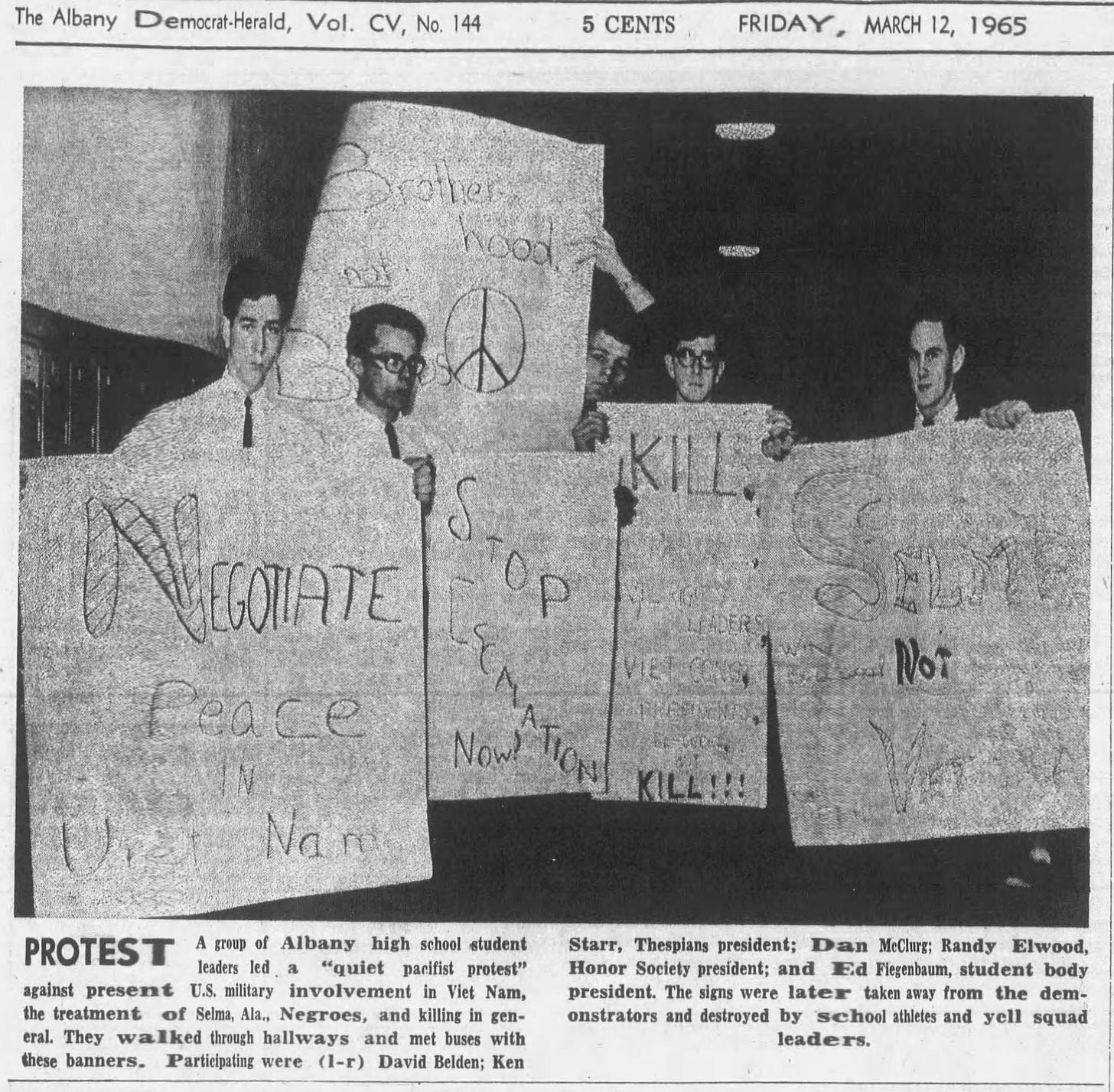

Two years later, in their senior year, Belden and McClurg staged an anti-Vietnam War and pro-Civil Rights protest by silently walking around the halls of their school holding signs. The result was that “athletes and yell squad leaders” took their signs away and destroyed them, presumably with the approbation of school officials including, most likely, McClurg’s former football coach and US History teacher. Ken Goff couldn’t have been more pleased with the behavior of the “good people” of Albany. Even though those “good people” perhaps didn’t entirely endorse Ken Goff' and Walter Huss’s view of the world, their actions signaled that they considered protesting against these white Christian nationalists to be more offensive than what those racist and antisemitic “Christian Patriots” had to say.

Albany Democrat-Herald, 12 March 1965

The question I was most eager to ask David Belden was how he and his friends knew about the 1963 Huss/Goff lecture and why they decided to attend. The answer led me fascinating places I could have never imagined.

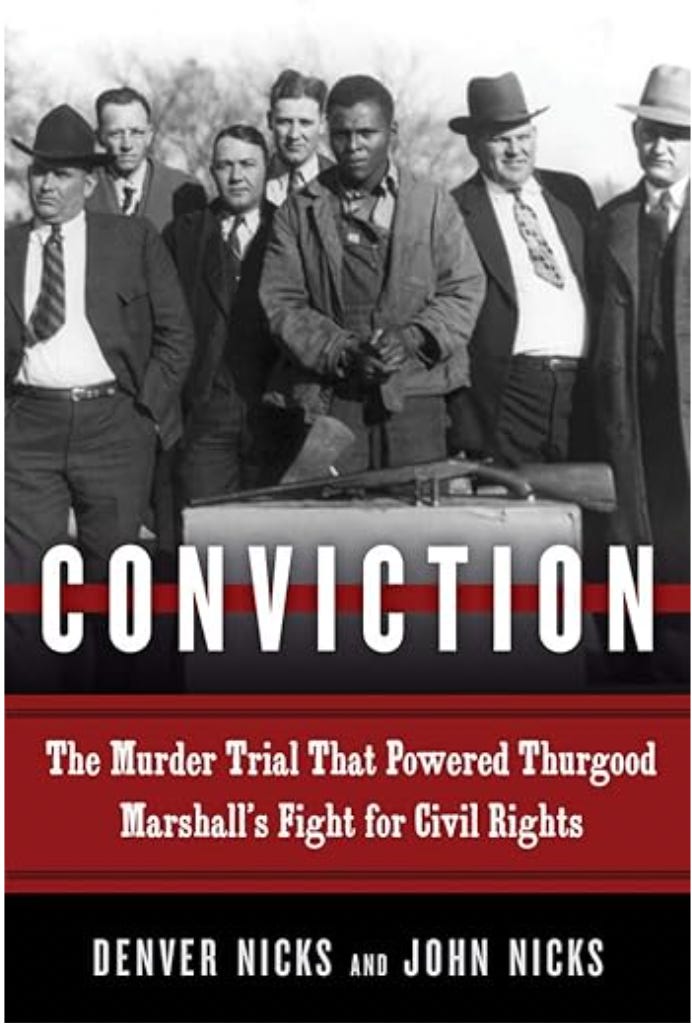

While Belden’s friends came from families with a range of political commitments (most being moderate or liberal Democrats), Belden’s family stood out in Albany for the depth and extent of their progressivism. The family had moved to Oregon from Oklahoma in the 1950s because Belden’s father Stanley, born in 1898 to Socialist sharecropper parents in Kansas (a less uncommon demographic than you might think), had been run out of Oklahoma in the McCarthy era for the offense of serving as a defense lawyer for a Black man named Willie D. Lyons who’d been framed by local white elites for a murder he did not commit.

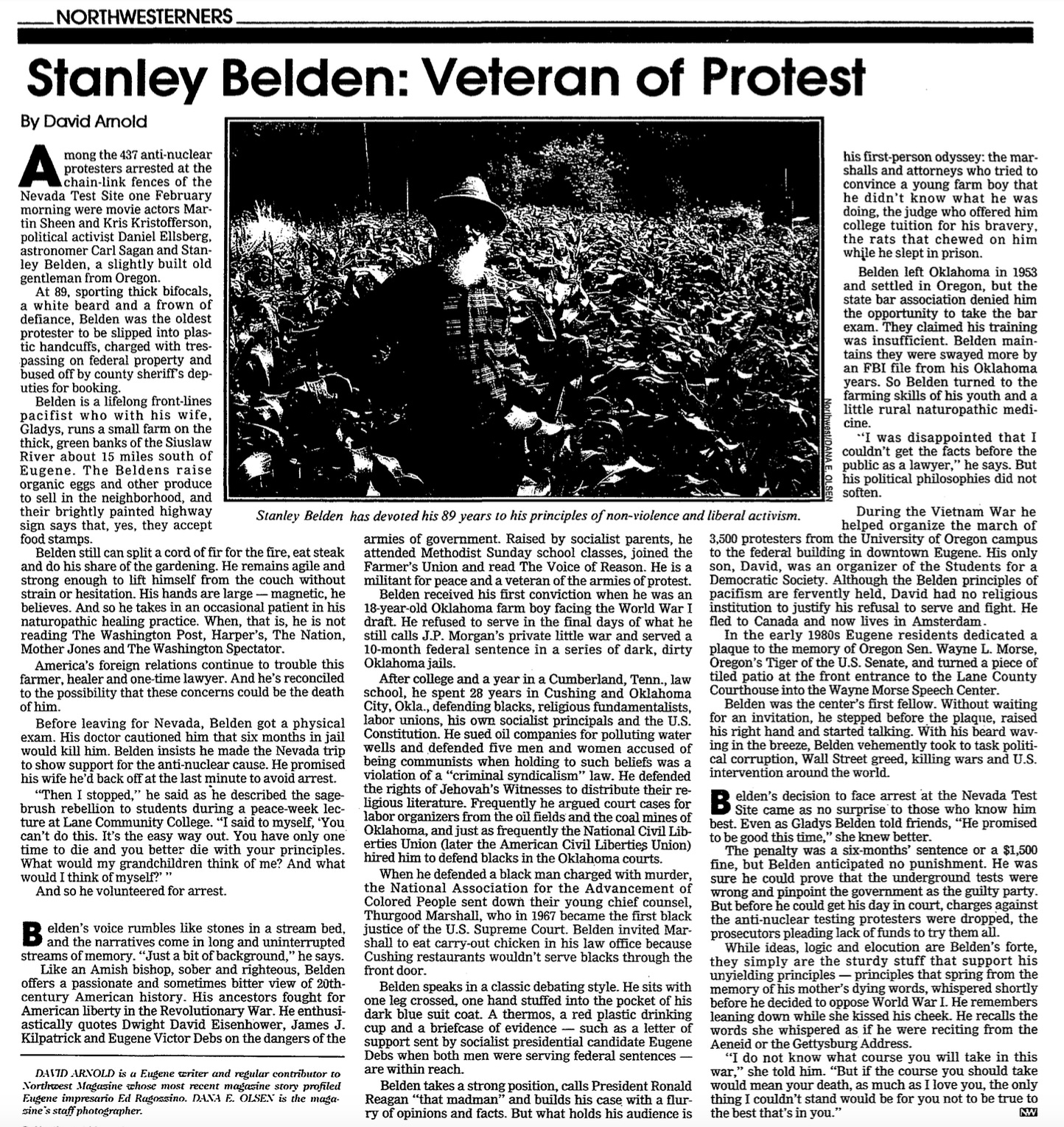

Belden worked in tandem with the Oklahoma NAACP and Thurgood Marshall on that WWII-era case, and that experience was a key turning point in Marshall’s career as a civil rights lawyer and then jurist. But as we see in this 1987 Oregonian profile of Stanley Belden, that was just one of many notable moments in his career as a grassroots progressive activist.

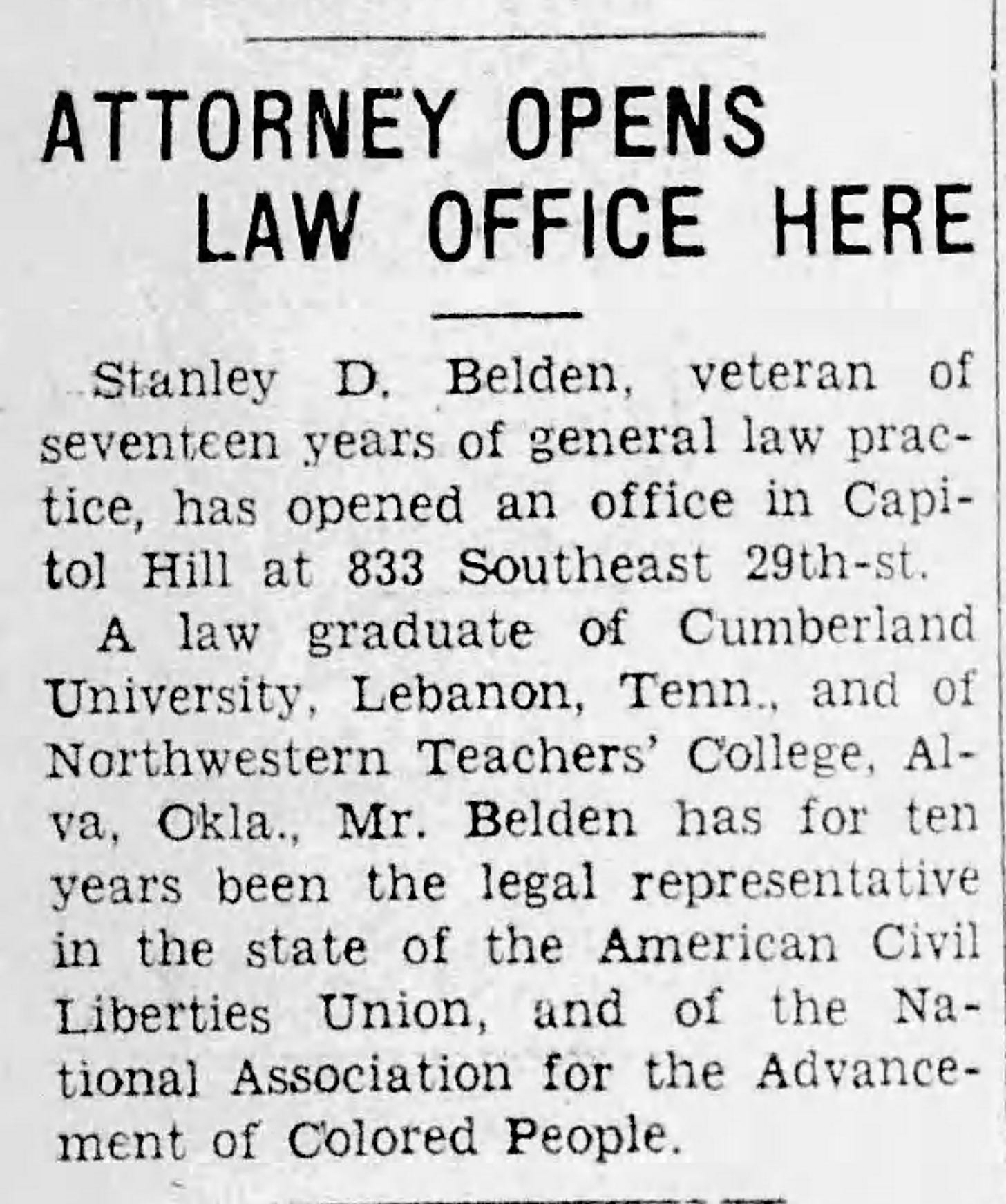

Stanley Belden was a principled pacifist, but there was one time in his life when he consented to join the US military, and that was during WWII when he signed up to fight against fascism. His career traced an arc from exchanging letters with Eugene Debs in 1918 while serving time in jail for refusing to serve in WWI, to protesting nuclear testing in the Nevada desert in 1987. In between he served as the lead lawyer for the ACLU and the NAACP in Oklahoma in the 1940s, as the head of the Albany, OR PTA in 1960, and as an organic farmer who accepted food stamps for eggs on the weekdays and drove to Eugene on weekends to protest the Vietnam War draft.

[Oklahoma City] Capitol Hill Beacon, 31 March 1942

Albany Democrat-Herald, 17 October 1968

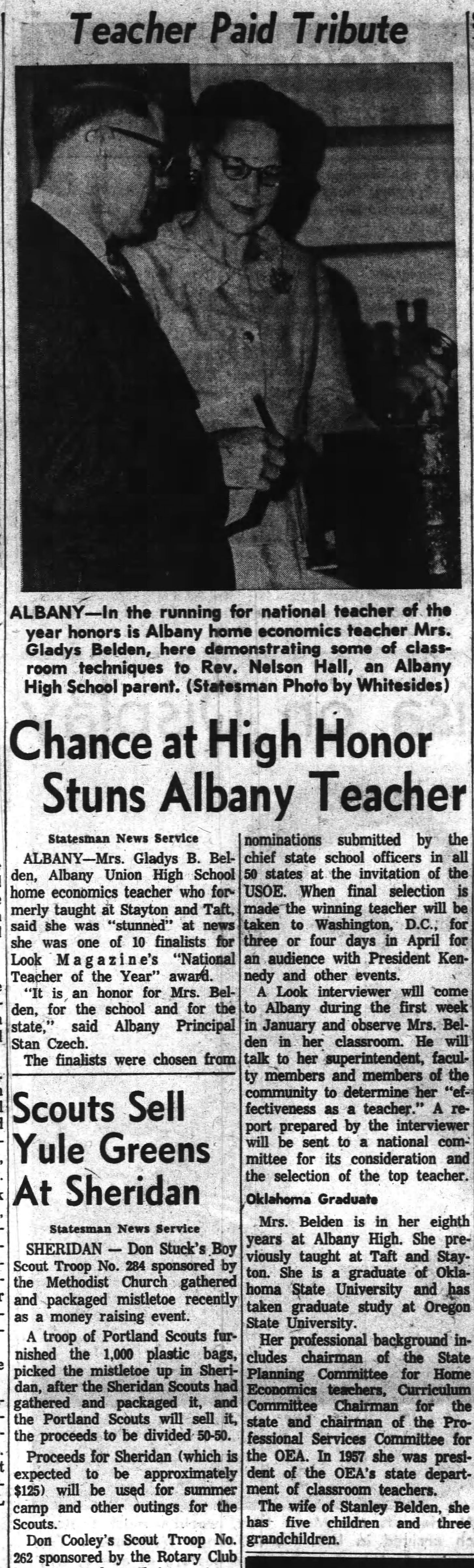

David Belden’s mother was just as important an influence in her son’s life. She was a beloved Home Economics teacher at Albany High who in 1962 was nominated as one of the nation’s ten best teachers by Look Magazine. David proudly told me that his mother taught students about birth control in her conservative Albany high school in the 1950s and 1960s.

Salem Statesman Journal, 21 December 1962

Before she and Stanley had been forced to leave Oklahoma, Gladys was a very active member of her local community. In the article below, for example, we see her giving a 1951 talk on “The Unfinished Business of Democracy” to the AAUW group in Seminole, OK, a town of 11,000 people about 60 miles SE of Oklahoma City. I want to emphasize that these grassroots democratic activists in Albany, OR had attended regional public colleges in Oklahoma and had grown up rural and working class…this is not a story about snooty “east coast elites” imposing their alien values on “authentic rural Americans” in either Oklahoma or Oregon.

Seminole [OK] Producer, 8 May 1951.

David Belden described the political culture of Albany ca. 1963-65 as quite polarized, especially around the election of 1964 when Goldwater fired up the town’s self-described “conservatives,” especially the ones allied with Huss and Goff who strenuously opposed the Civil Rights Act. Meanwhile, many young people like Belden were becoming politicized by the music and movements of the 1960s. One of his classmates who came with him to Eugene to see Goff, for example, was a relatively apolitical person who found their way into the counter culture via a love of modern jazz and folk music. When I asked Belden if his political activism caused any problems for him in his social life he told me how his girlfriend’s father, a prominent conservative doctor in town, “threatened to castrate me with a rusty can opener.”

Stories like these are a useful reminder, especially to more progressive folks who live in Trump Country, that the atmosphere of intimidation and menace that often hangs over such places today is neither unprecedented, nor a permanently unchanging feature of our political landscape. It is my hope that stories about what Belden and his classmates did can in some small way embolden us to engage in pro-democratic protest as they did, to take a stand on what in hindsight seems to fairly clearly be “the right side of history.” There are Stanley and Gladys Beldens in every community. We should remember their pro-democratic advocacy as having been just as authentically “American” as the anti-democratic activism of figures like Huss and Goff or the reactionary stubbornness of Dan McClurg’s football coach.

Another surprising turn in the story

About midway through our zoom conversation Belden directed my attention to a flag of honor on the bookshelf behind him. It was given to him by his son, a Green Beret who served in the Iraq War, became radicalized in the military, and is now a Qanon believer and militia member who was arrested in 2020 for aggressively interfering with a Black Lives Matter protest in Montana. A facile (and incorrect, IMO) interpretation of this twist in the story would go something like this: extremists on the left and the right are more similar to each other than they are different, and so this is a story about the continuity of inter-generational extremism in this family. David Belden turned up unwanted at a conservative gathering in 1963 and found some trouble, and his son turned up unwanted at a leftist gathering in 2020 and found some trouble. Just two sides of the same coin, right? I don’t think so.

In contrast to that interpretation, I would hypothesize that this has much more to do with how specific historical moments and political cultures shape the individuals who are socialized into them. Stanley Belden was very much a product of the early 20th century rural Socialist culture he grew up in. His son David was socialized by his progressive parents, but also by his chosen cohort of friends and the political culture of his era —the protest music of people like Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, the moral force of the civil rights movement, and the student movement that emerged in opposition to the Vietnam War. The politics of his son, the Montana Militia member from whom he is now sadly estranged, resemble that of many former military men who have been actively recruited by white supremacist or far right groups over the past few decades. While most studies have found that military veterans are represented in far right extremist groups at the same rate as the general population, it was Belden’s impression that his son’s experience in the military played a role in pushing his politics toward the far right.

Political cultures—like that of ultra-MAGA Trumpism—don’t just reflect the pre-existing worldviews of the people who inhabit them, they also function as behavioral guidebooks and permission structures that actively shape and sometimes significantly transform the people who get involved with them. This politicizing dynamic is not necessarily good or bad, pro- or anti-democratic. Participating in social movements like the civil rights movement or the feminist movement or the LGBTQ movement, for example, was often a life-transforming experience that inspired people to commit themselves to the cause of democratic change and social justice.

But we’re also sadly familiar today with how the Qanon movement has ripped families apart and destroyed the lives of many of its adherents, or how the activism of far right Moms for Liberty groups have made the lives of school administrators and librarians a living hell and stoked significant anger and division in local communities. Likewise, the Trumpian Republican Party today socializes young Republicans into a culture of conspiracy-obsessed, apocalyptic far right illiberalism. To be a 20 year old conservative who thinks and talks like George Will or Mitt Romney did back in the 1970s is almost unthinkable…not because those ideas are unthinkable but because the political culture of the contemporary conservative movement has become inhospitable to that variety of “conservatism.” I’d argue that the default culture amongst current GOP activists is more closely aligned with the angry and apocalyptic illiberalism of conspiracy aficionados like Walter Huss or Kenneth Goff—figures who a young George Will or Mitt Romney would have regarded as “fringe kooks” in the 1960s.

We live in an era when far right extremism is in ascendance, just as it was in the early 1960s when David Belden decided to learn about it and speak out against it. It’s a sad irony that Belden’s son is now attending conspiracy-saturated meetings of angry and violent self-described “Patriots” much like the one he was chased out of in 1963. It’s a testament to the durability of America’s far right anti-democratic tradition. But it’s also a reminder that despite that subculture’s deep roots, it’s always been just one strand among many, and a strand that many generations of Americans have pushed back against in a variety of ways.

One last twist

Almost the entire town of Hugo, Oklahoma turned out to watch the trial of Willie D. Lyons in 1941. Despite the best efforts of Stanley Belden and Thurgood Marshall, Lyons was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison. One notable feature of the trial, however, was that the majority of white people who witnessed it (apart from the people on the jury) were persuaded that Lyons had been railroaded by corrupt local officials who were trying to cover up for their own malfeasance in having released from prison the white bootleggers who actually committed the murder. In the next election, the town voted out the Sheriff and other local officials who’d been responsible for the injustice done to Lyons. Roscoe Dunjee, the head of the Oklahoma NAACP who ran The Black Dispatch newspaper in Oklahoma City, reported that during a break in the trial a white farmer with muddy boots and hardened hands walked up to him and thanked him for his efforts on Lyons’s behalf. These small moments of white rural dissent from the racist behavior of local white elites were not enough to secure justice for Willie D. Lyons, but they do point to the complexities of the situation on the ground, the fragility of white supremacy, and the impact that people like Belden, Marshall, and Dunjee had on the political climate of that town.

It’s also important to note that Stanley Belden had to flee Oklahoma after that trial not because he was run out of the state by a pitchfork wielding mob, but because local elites refused to do business with him as a way to punish him for his defense of Willie D. Lyons and his treason against white supremacy. It wasn’t Oklahoma as a united mass that drove him out, for as we’ve seen, the people in the small town where the murder occurred seem to have appreciated Belden’s efforts to defend their innocent neighbor. When Belden moved to California he hoped to find work as a lawyer. But because he needed a letter from the Oklahoma bar to practice in California and because the head of the Oklahoma bar happened to be a white supremacist member of the conservative American Legion who refused to give Belden such a letter, Belden’s career as a lawyer came to an end and he eventually found work in the early 1950s managing a hop farm in rural Oregon. Another reminder that institutions matter, and that the character of the people in positions of power and authority in those institutions also matter.

Great piece! And thanks for referencing the "Bring The War Home" mentality that has focused on recruiting active-duty servicemembers into rightwing causes.

Thank you for this!