"Right wing nuts" for Reagan: A conversation between Thomas Zimmer, me, and Ben Bradford, the maker of the "Landslide" podcast

NPR recently released an excellent podcast series on the politics of the 1970s called Landslide. If you haven’t listened to it yet, I highly recommend it. At the very least, it’ll almost certainly revolutionize the way you think about Gerald Ford. [How about that for the hard sell?] But seriously, it’s a very engaging, informed, and insightful analysis that proposes some compelling historical genealogies for our current political moment. The podcast’s account of national politics also tracks with the interpretation of Oregon political history I’ve been developing here on this newsletter.

Earlier this week I got a chance to speak with the journalist behind that podcast, Ben Bradford, along with my friend and fellow historian Thomas Zimmer. So if something as meta as listening to a podcast…about a podcast…about history is your sort of thing—and if you’re a subscriber to Rightlandia then I suspect you just might be in that admittedly niche demographic—then here it is for your listening pleasure. We spoke for almost two hours. This is the first half of the conversation with the second half to follow next week.

I want to take some time to expand on one theme that emerges in Landslide and in our conversation about it—the extent to which the Reagan phenomenon in 1976 and 1980 was powered by a collection of “right wing nuts” who had previously been fairly marginal players in GOP politics and who looked like deeply unserious freaks to experienced politicians like Gerald Ford and his team. This speaks to the sociological and ideological dimensions of the gradual right wing take over of the GOP—the extent to which right wing insurgents like Walter Huss represented elements of American society that establishment Republicans regarded as profoundly foreign, strange, and ultimately (but incorrectly) inconsequential.

These insurgents sounded “weird” to mainstream Republicans because most of them rejected at least a few of the basic tenets of that era’s putative (small l) liberal consensus—that government regulation in the public interest was necessary in a complicated modern society, that the US was a religiously pluralistic society that privileged no particular faith tradition, that America was a nation shared equally by all regardless of race or ethnicity, and that women and men should be treated as equals under the law. The anti-government extremists, religious bigots, white supremacists, and rank misogynists were all supposed to be fading away into the mists of history…sure, some old “crackpots” might still believe that stuff, but “nuts” like that could never get organized enough to take over the Party of Lincoln, could they?

Such was the view from inside the quite constricted social world of those old “country club Republicans.” Such people weren’t stupid, they knew there was plenty of nasty illiberalism floating around out there in American society, it just didn’t seem plausible to them that such crankery could coalesce into a political movement. We certainly can’t blame these GOP moderates for lacking the hindsight that we today have, but we can ask questions about why they interpreted their political moment in the way they did, and why they perceived some aspects of their historical moment accurately while missing other features entirely.

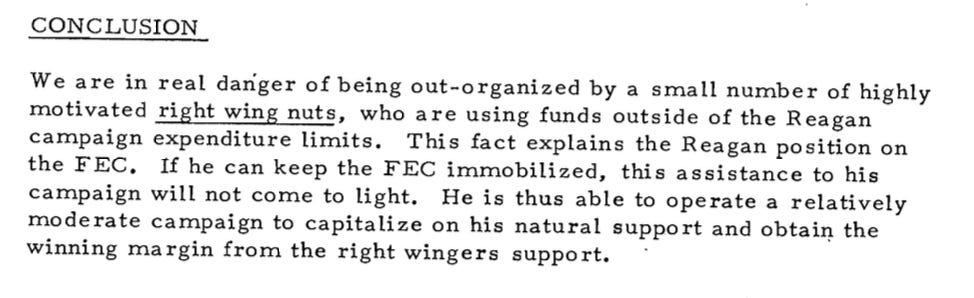

In Episode 3 of Landslide, “The New Right,” Ben draws our attention to an amazing Ford campaign memo from the 1976 GOP primary in which the unnamed author laments that the Ford campaign was at risk of being “out-organized by...[the] highly motivated right wing nuts” whose energies were powering Reagan’s challenge to the sitting president. The term “nuts” here is noteworthy, because it captures the shocked disdain with which moderate Republicans like Ford looked upon the far right insurgents who were trying to muscle their way into the driver’s seat of his party.

We now know that the phenomenon described here—only the bare outlines of which were visible to the memo’s author at the time—was the “the New Right” and the avalanche of scaremongering and culture-warring “direct mail” pioneered by Richard Viguerie. This reactionary and apocalyptic messaging played a significant role in drawing into the Republican coalition the new demographics of “George Wallace voters” and “socially reactionary, non-mainline white Protestants” who had never been reliable GOP voters before.

As episode 5 of Landslide reminds us, George Wallace (the “segregation forever” guy and former Governor of Alabama) had garnered a ton of support in the 1972 Democratic primary and in 1976 he was still considered a formidable force in the Democratic primaries in the South. Indeed, one important story line in the 1976 Democratic primaries was that other candidates chose NOT to run in Florida so that Carter, the white southerner, could take on Wallace head-to-head, defeat him, and thereby push him out of the race and banish Wallace’s brand of politics from the Democratic coalition for good. Many Democrats feared that Wallace could win the Florida primary if the anti-Wallace vote was spread across many other challengers, and that a Florida win might put Wallace on a plausible path to the Democratic nomination. Take a second to imagine an alternative timeline in which the Democratic nominee in ‘76 was George Wallace, who would have then likely been trounced by Gerald Ford.

Looking back from our 2024 vantage point, the pugnaciously anti-media, anti-intellectual, and anti-liberal George Wallace of 1964, 1968, 1972, and 1976 looks like an obvious precursor to the Trumpian brand of Republicanism. In 1976, however, it was not entirely clear that the GOP would eventually provide a comfortable home for such right wing populism. It was Reagan, working together in the ‘76 primary with a host of Wallace-friendly New Right activists like Tom Ellis and Richard Viguerie, who cemented that connection.

The place where Reagan’s appeal to “the Wallace vote” became most apparent was in the 1976 Texas primary. At that point in the race Ford seemed certain to coast to victory in the primary. But the Reagan campaign, which had recently scored a surprise victory in the NC primary using the race-baiting tactics of Jesse Helms’s eugenicist associate Tom Ellis, decided to go all in to try to win the Texas primary. Their strategy was to invite the historically Democratic “George Wallace vote” to cross party lines (now that Wallace had been pushed out of the Democratic primary by Carter) and vote for Reagan in the GOP primary. It worked…thus inspiring that Ford campaign memo mentioned above decrying how all of these outlandish “right wing nuts” had begun to wield influence in a Republican Party that by rights should belong to more socially moderate politicians like Gerry Ford and his VP Nelson Rockefeller.

Ultimately, of course, Gerald Ford successfully beat back the Reagan primary challenge led by those “right wing nuts” in 1976, but we all know what happened in 1980 and after.

Why didn’t Oregon’s moderate Republicans do more to fight back against that “right wing nut” Walter Huss who stole their party out from under them?

While Landslide tells the story of the ultimate triumph of these “right wing nuts” at the national level, there’s value in seeing how that same story played out at the state and local level. Indeed, that’s the entire premise of my research into Walter Huss—that we can get a clearer and fuller understanding of how the Republican Party moved to the right over time by looking at local activists like Huss who drove that transformation. While Huss is the particular focus of my research, he’s surely just one “right wing nut” amongst many whose actions shaped the political culture of their state GOPs, but whose stories are, at this point, not well known.

Just as the Ford camp incredulously shook their heads at the sight of the culture warring anti-ERA, anti-abortion, and anti-civil rights constituencies who were riding into the GOP on the Reagan wave in 1976, that same sense of shocked disbelief marked how the historically moderate Oregon Republican establishment looked upon Huss’s elevation to party chairman in August 1978. Huss’s victory was so shocking and newsworthy that it earned a write up in the Washington Post.

To what extent did Oregon’s moderate Republicans see the triumph of a “right wing nut” like Huss coming? And what, if anything, did they do to try to stave it off? Finding straightforward answers to these questions has been far more challenging than I had initially thought.

I began my research into Huss’s 1978 victory by scouring the Oregon Historical Society’s huge collection of oral histories for mentions of Huss. The OHS interviewed scores of people who’d played prominent roles in Oregon Republican politics during Huss’s time, but for the most part, those people had very little of substance to say about Huss and his insurgency. Several people complained about how much they disliked Huss, but they didn’t have much to say beyond that.

For example, in the late 1990s Mark Hatfield sat down for several days of oral history interviews, the transcription of which takes up over 900 pages. He mentioned Huss exactly one time. One of Hatfield’s major preoccupations in the late 1990s was the sad, increasingly right wing state of the Republican Party at both the national and state level…and yet he had zero interest in talking about the right wing activist who’d been a Hatfield-hating burr under his saddle since the early 1960s and who took control of the OR GOP in 1978, a year when Hatfield was running for re-election. One obvious answer to Hatfield’s pressing question of “how did the GOP get like this?” had been right there all along, sniping at him from his Freedom Center headquarters in SE Portland on a regular basis for forty years, and yet in Hatfield’s memory Huss loomed about as large as a case of food poisoning he got from a bad piece of fish he ate at a campaign event once.

Hatfield’s fellow establishment Republican Wendall Wyatt had only slightly more to say about Huss. Starting at minute 27 in this 1988 interview, for example, we hear Wyatt talk about how Huss didn’t have much support amongst Oregon Republicans but just sort of snuck up on and surprised normie Republicans like him in 1978 when he won the election for state party chair. Around the 5:30 mark in this interview Wyatt recounts a conversation he had with Gerald Ford in 1978 or ‘79 where Ford asks if the OR GOP had gotten the problem with “that nut [Huss] resolved.” Speaking at a time when it seemed, to Wyatt at least, that the more reasonable Republicans had taken back the party by nominating George HW Bush, Huss’s insurgency seemed like a temporary, annoying blip in what was otherwise a history of GOP moderation.

So on one hand, what we hear in oral histories from moderate Oregon Republicans like Wyatt is that Huss’s 1978 victory came as a shock. Who could have seen it coming? But on the other hand, there are voices like that of Richard Jones, a manager for many of Hatfield’s campaigns. Jones recalls a prominent Oregon Republican warning him in 1968 that the far right forces, under the leadership of Walter Huss, were slowly taking over the state party at the precinct and county level. [You can hear him saying this at the 7:50 mark of this interview.] As I’ve argued in the newsletter linked below, Huss’s far right grassroots insurgency to take over the OR GOP had actually begun in 1962, a full 16 years before it bore fruit with his ascendence to the chair.

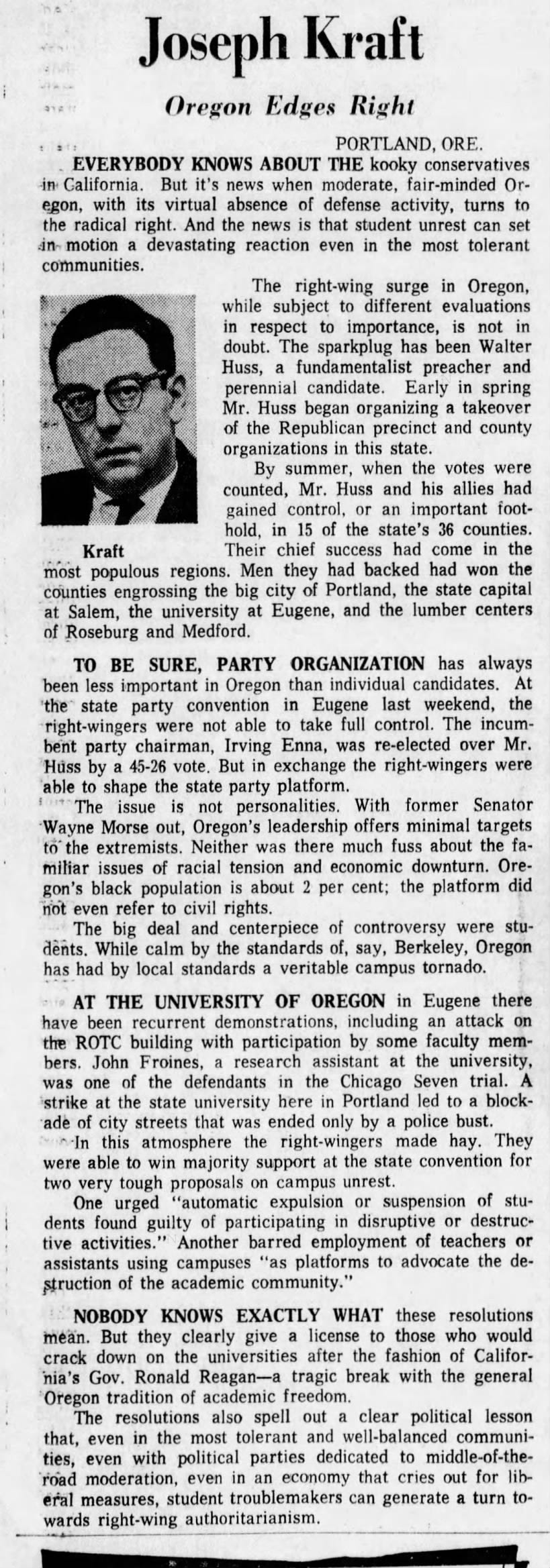

Where the oral histories (mostly conducted in the 1990s) with former establishment Republicans have precious little information or insight about how Huss managed to steal the party out from under them, the newspapers from the 1960s and 70s mentioned the rising far right inside the OR GOP fairly often. For example, here’s a nationally-syndicated column from 1970 noting Huss’s growing influence in the OR GOP.

And here’s a UPI report from 1970 that also appeared in newspapers in many different states.

When I interviewed Roger Martin, a very influential moderate Republican who was active in the 1970s, he told me a pretty funny story about the 1970 OR GOP convention in Eugene. Huss had rented out a suite on the top floor of the hotel so he could get his troops organized for an attempted takeover. The night before the vote, Martin and his establishment friends ordered a ton of food and drinks for themselves via room service and then had the bill sent up to Huss’s suite. Huss was apparently quite apoplectic about this offense, in part because he was a teetotaler. So while Republicans like Roger Martin may have considered Huss pathetic and prank-worthy, it’s not as if they were unaware of his existence.

A couple years later, in 1972 or ‘73, the state’s leading contractors hired someone to work full time trying to recruit moderate (and hence electable) Republican candidates for the upcoming election cycles. They did this in order to counteract the “nuts” who Huss’s forces were recruiting to run for office. Again, these are wealthy and powerful Republicans spending a good amount of money to fend off Huss’s insurgency five years before he eventually became party chairman. So when these same Republicans in the 1980s and 90s remember Huss’s victory as “a surprise” that “came out of nowhere,” what are we to make of that? Perhaps they were just lying to make themselves look better, but I don’t think that’s the full story.

Far from being some unknown quantity who snuck up on the moderate OR GOP in 1978, Walter Huss was very much on the radar of the state’s Republican establishment. Calling him “a nut” and playing pranks on him at the state convention may have felt good to such people, but it did nothing to actually counteract the increasing and malign influence Huss and his followers were having on the party.

Again, it’s very important to recognize that hindsight is 20/20. The point isn’t that there was some obvious thing that moderate Oregon Republicans should have done but didn’t that would have thwarted the rising far right in their party. Rather, I’m still puzzling through the question of why they were seemingly blindsided by something as monumental as the takeover of their party by people who rejected the foundational values on which they thought the Republican Party (and the US) were based. Not only did they not take that threat seriously enough at the time, they also seem to have had little understanding of it in hindsight.

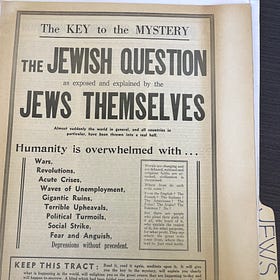

This is still a fairly undeveloped thought but I’m going to throw it out there as a way to wrap this up…I think Huss was so illegible to them, a figure they were just incapable of integrating into their understanding of American politics, because at some unconscious level they recognized that Huss was a fabulist and a fascist, and that was just too terrifying to take to heart. I mean, what does it say about the Republican Party to which you’ve dedicated your entire life when a conspiracy-obsessed, Holocaust-denying white supremacist and vicious antisemite who was devoted to the fascistic politics of “participatory anti-democracy” wins election to be its chair?

"Silver Shirts for Reagan!": Walter Huss and the American "conservative" tradition with roots in 1930s-era fascism

I can understand why such people would see Huss’s win as an aberration, something that genuinely did not reflect their values. There was much truth to that, but then again, Huss (a very enthusiastic Reagan delegate in 1976 and 1980) became the chair because he inspired a critical mass of actually existing Oregon Republicans to vote for him and reject the party’s establishment. Calling such a person “a nut” doesn’t take us very far toward an accurate analysis of what was going on inside the OR GOP in the 1970s and 1980s. And if one was a Huss-hating Republican in that era, one would have thought his insurgency would have provoked a bit more sober analysis to go along with those rhetorical denunciations.

Revolutionize the way we think about Gerald Ford! Sooooooooo excited!

Most of your readers are podcast nerds like me so you're probably right. That's pretty sad. ;)